Fakes are becoming increasingly frequent towards the end of this century. The author has found 80% over all areas of art, a percentage that should be “decreased to reflect the national market which, depending on the sector, is approximately 50% because objects that are not contested by experts are not the subject of examination”. To illustrate this introduction, the authors present, by way of example, the detection of a fake Rembrandt, having successively studied the aspect, the frame, cracks, the signature and retouchings. They then examine copying and the science of pastiche.

La Revue Experts no. 13 – 12/1991 © Revue Experts

by Gilles PERRAULT and Philippe LAURENT

Fakes are becoming increasingly frequent towards the end of this century. The substantial fluctuations in the art market have given rise to numerous vocations and have revived the interest of forgers… The statistics from my Expertise Laboratory are alarming because on average we find 80% of fakes over all areas of art!… This percentage should, however, be decreased to reflect the national market, which, depending on the sector, is approximately 50% because objects that are not contested by experts are not the subject of examination.

The object that we are presenting to you today is an example of a category of fakes of older paintings that we studied in the Laboratory that was restored by Philippe Laurent, a former restorer at the Versailles Palace. It begins a series of articles on the detection of fakes that we will develop in various areas of art in following issues, together with other authors.

Rembrandt Van Rijn, “Self-portrait”

Cette toile se présentait comme un Rembrandt, seule une expertise minutieuse, que nous allons développer, a permis de détecter la supercherie.

An Illusionary Work

The painting has numerous cracks, is on an old canvas woven from a manual loom (photo 1).

The pine frame contains two customs stamps (photo 2). While not of that era, it is ‘old’. The side of the painting shows that it is a format reduction ‘retention’, which, unfortunately, is not uncommon (photo 3).

Clearly the painting has been subject to cleaning that has worn down the pictorial layer, but that also frequently occurs! In examining it in more detail, brush strokes are discernable on the undercoat of the neckline and the right hand that holds the face has been hidden but remains barely visible. These are undoubtedly modifications made by the master painter during the creation of the work that are called ‘retouchings’.

|

|

|

||

| 1 – Side of the canvas showing the weaving | 2 – Customs stamp in one corner of the frame | 3 – Edge showing the pictorial layer remaining after affixing |

This is good news because apparently only original works contain retouchings… It is then with some emotion that you remember a Rembrandt painting that you admired in the Taft Museum in Cincinnati (photo 4) painted a decade previously. This is clearly in the same format.

Another look at the signature, nearly in the middle of the painting, discrete, black on a dark reddy-brown, of good calligraphy.

All of this encourages you to buy this touching work despite several inconsistencies in the master painter’s cap, for example; it is maybe a poor restoration that altered aspects of the object!

So, if your purse permits, you will become the owner of… a fake!

We are, in fact, looking at a portrait created along the lines of the Rembrandt Self-portrait that is dated between 1665-1669 on a 82 x 63 cm canvas held by the Wallcraf Richartz Museum in Cologne (photo 5).

|

| 4 – Self-portrait, Taft Museum in Cincinnati |

Our painting represents only the upper half of the artist and ignores the standing figure that is to the left in the original canvas.

It is a type of monochrome: unlike the original, the face does not contain the subtle variations in colours that enabled the artist to structure the complexions; here, we have a succession of ochres applied with rather soft brush strokes that are ‘oily’ and lack transparency, which gives it a slightly ‘blurred’ appearance. Rembrandt had a sure, audacious, touch that played on the transparency and the complementarities of the colours. His drawing is precise despite the interpenetration of the brush strokes: no limits, but a highly skilled sharpness, a perfect representation of volumes providing significant subtlety in contrasts.

Our painter plays with the lighting to give the illusion of volume. For Rembrandt, it is ‘painted’ and the light reinforces the rendering to situate it within the work as a whole: it arises out of the obscurity.

The Signature

The signature in our work is of good calligraphy: black on a dark brown background, discrete but visible. However, its positioning is somewhat troubling: nearly central, under the artist’s chin and the date overlays the collar of the clothes.

Clearly, in that era, the positioning of a signature was unrestricted, but the tendency in the 17th century, when the signature was applied, was never to overlay the clothes worn by the person whose portrait was being painted.

The calligraphy provides us with some precious information: in 1664, Rembrandt is old and his illness is reflected in his signatures, which become very irregular, uncertain, even shaky. A signature, however, should not be an absolute element of authenticity because it can be contemporary with the work but added by a third party.

Madeleine Hours, in her book Le secret des Chefs d’Oeuvre, recounts a revealing anecdote. In its reserves, the Louvre Museum has a painting that is attributed to Chardin, Les apprêts du pot-au-feu. This painting, after having been sent off for an exhibition, became the subject of a rigorous examination in order to precisely determine its overall condition. An infrared light reveals an inscription hidden by glaze. Taking the glaze off, the word ‘Bounieu’ can be seen: a forgotten painter who was, nevertheless, a rival of Chardin at the Royal Painting Academy in the 18th century. But is he well-known today?

Sometimes the work is authentic, the signature false, but still…

In relation to the signing of a work, all combinations are possible depending on the creativity of the forgers who, it is clear, are highly skilled and have access to substantial resources.

Do not forget, however, that the more a signature is contemporary with the work, the more difficult it will be to prove its authenticity.

Ageless Cracks

The portrait that interests us has an old, somewhat ‘used’ aspect to it. The network of cracks would appear, at first sight, to be normal. The painting has not been re-canvassed, the pictorial layer retains its flakes in ‘hollows’.

From a first, attentive, observation, we notice that we are dealing with ‘impasto’ cracks over the entire pictorial layer that are characteristic of over-painting.

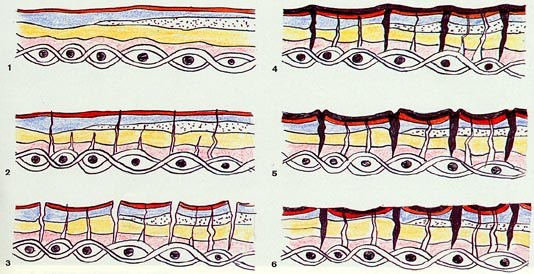

A network of cracks in an original 17th-century painting is always definite, with sharp crests. The diagram below illustrates how such cracks are formed.

The painting and preparation of a recently executed painting is supple and, as such, unaffected by the variations in tension provoked by heat and humidity (illustration 1).

|

But, over the years, the constructive elements of a work become more and more rigid until they break. A sort of ‘mineralisation’ of such elements occurs. The preparation of the canvas is the first aspect to become rigid, despite the additives used to render it more supple. For example, Venetian turpentine, fluid when used, becomes very brittle after approximately fifty years.

It is only by using chemical drying agents that the process is reversed: until the 18th century, the fissuring of the preparation led to the formation of cracks in the pictorial layer whereas in the 19th century, the cracks occur in the paint layer well before the fissuring of the preparation.

With each movement of the painting, each tension (in the larger cracks), ruptures are produced that are visible on the surface and end up covering the entire painting (illustration 2).

The surface tension of the painting transforms into ‘islands’ and ‘hollows’ (illustration 3).

When a cracked surface is painted over, the network of cracks is covered by a new layer of paint that initially effaces it (illustration 4).

An artificial aging process enables the cracks to reappear, just like the initial cracks (illustration 5). To successfully execute this trick, the forger uses a paint that has a significant quantity of drying agents and adds resin. Placing the painting in an oven will enable a better definition of the new network of cracks.

To complete his work, the forger sometimes scrapes the pictorial layer. The abrasion of the crests and hollows reveals the lower layers but leaves a line of the over-painted colour in the middle of the crack that is visible using a microscope (illustration 6). This is the case with our painting.

The Retouchings

As paint gets older, it mineralizes and becomes less and less opaque to become somewhat transparent. When the artist changes the composition, all modifications reappear over time: these are ‘retouchings’. Very often, they are in the same hue as the detail being corrected. Sometimes the artist deliberately changes the particular hue of an area, but the retouching always follows the dynamic of the detail being retouched.

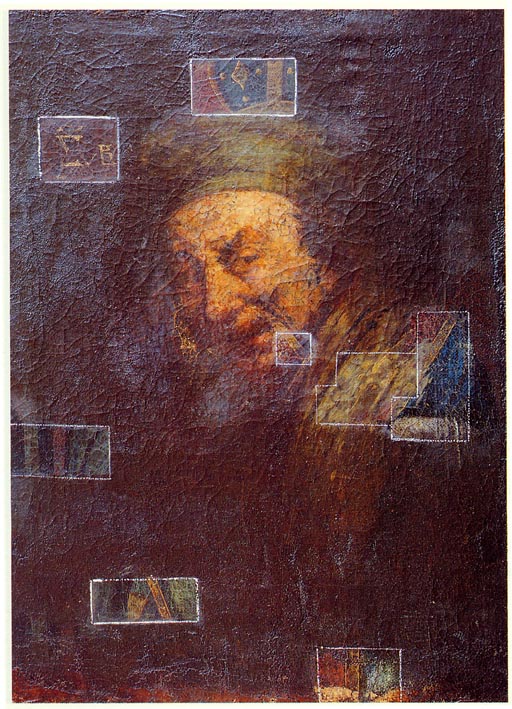

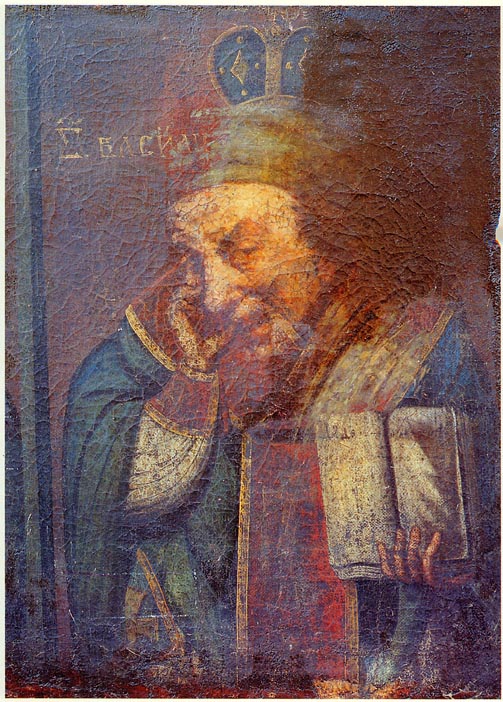

Our Rembrandt self-portrait has some ‘retouchings’ that do not follow the visible drawing of the subject, the various colours and the reliefs. We are, therefore, in the presence of the superimposing of two completely distinct paintings. One window shows an inscription in Cyrillic characters and a different origin. A more detailed clearing above the wig reveals a tiara. Several windows that were cleared in areas chosen not to harm the work (photo 6) confirms the hypothesis posed and, in addition, show that we are in the presence of two totally different techniques.

This finding is particularly noticeable in the probing carried out in the lower left-hand side of the painting, where no detailed painting exists but where, by oblique light, the brush-stroke relief appears in the underlying layers.

The window reveals colours and a drawing that have no relationship with the self-portrait. The same is found in the opening made to the right of the mouth of the master painter, being particularly visible.

These eight probes, carried out using a weak solvent (xylene-toluene), proved that the upper pictorial layer was recent because even the base white colours dissolved without difficulty.

After an x-ray was carried out and due to the quality of the original painting, it was decided that the over-painting be completely removed, with agreement from the owner.

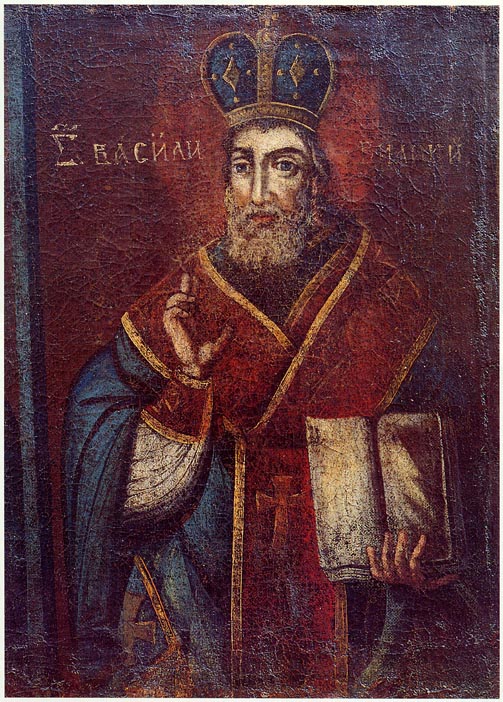

This example, being but one of the multiple facets of forgers, clearly reveals another painting that is, in fact, a 17th-century Russian painting representing Saint Basil (photo 8).

It might be suggested that Rembrandt, due to financial difficulties, had used a previously existing painting in order to do this portrait.

However, if that was the case, he would have repainted one of his own paintings. It is unlikely that he would have hidden the work of another artist, even partially, no matter what the skill of the latter.

If, therefore, Rembrandt had repainted one of his own paintings, there would be the same level of homogeneity in the materials with the same resistance to solvents. To attack a 17th-century painting, however, solvents with considerable active strength need to be used! In our case, we used only weak solvents.

Copying Famous Painters

A copy is an approximately faithful reproduction of an original. The copier does not make any changes. Only the format varies: the painting can be larger or smaller or only a detail of the work being copied is reproduced.

Copying was a common practice in workshops. Its aim was not simply didactic but also a means of ‘multiplying’ a masterpiece, portrait, etc.

Copying was an excellent means of learning the painting techniques used by famous painters. One of the most extraordinary is the copy by Raphaël of the The Marriage of the Virgin, a work by his master Le Pérugin (Brera Museum, Milan).

Didactic also the copies that Delacroix made of Rubens (Louvre Museum).

In the second case, engraving was the only means of reproduction and multiplication of, for example, portraits of sovereigns and notables at a time when photography did not exist.

Napoleon III continued the tradition by offering copies of older works to municipalities and parishes throughout the Empire. Currently, the purpose, with only rare exceptions, is especially lucrative.

The Science of The Pastiche

Pastiche is an exercise in style that can be placed above that of a copy as not only is it necessary to have adopted the technique used by the master painter but it is also important to have an understanding of his graphical work, because to create a pastiche is to create a painting that the master painter could have painted but never did.

While all of the constructive elements of the pastiche are reinvented, the pastiche (and the copy) are always anonymous in order not to be the subject of court proceedings.

Comment: the more the copy or the pastiche are contemporary to the original, the more difficult it will be to detect them because the pictorial materials will have the same aging or similar effects.

The greater the lapse of time between the pastiche and the original, the greater its aspects will be different: the network of cracks differs, the structural materials will not be the same, etc.

Another detail should be considered: the person copying or creating the pastiche will be more concentrated on the end result rather than its internal structure, “that invisible part that holds a significant but unconscious place in perceiving an original work”.

A Perfect Example of A Fake

It is created for the exclusively mercantile purpose of misleading and all means are appropriate in order to attain such goal: using old materials such as canvases, older paintings that are painted over, false signatures and artificial cracks, scraped materials and false restorations, etc.

The Rembrandt self-portrait is in the latter category: all of the constructive elements of the painting have been deliberately used for the purposes of misleading. It has an old frame that belongs to another work and has two customs stamps.

A religious painting representing Saint Basil, cut and reset into this old frame, shows that the original painting exists and is partially preserved despite the mechanical effects caused by the tension in the frame. The forger used the process of false retouching, leaving some of the original aspects of the religious painting appear after scraping: for example, the hand holding the face resembles that of a portrait of Rembrandt…

With a false signature, the calligraphy of which does not correspond to the date of the painting.

And use of false damage followed by its ‘restoration’.

The Wrong Muse

Photo 7 was taken when the fake was revealed. The restorer, in re-establishing artistic verity, cannot hold back from being sensitive to the disappearance of the image presented to him, even if the result is a fake. The latter restraint enlightens us as to the elaboration of this fake.

The forger wanted to use all of the structural elements of the portrait of Saint Basil because it is a painting from the 17th century but also wanted to use certain details such as, for example, the hand of the saint and the collar of his clothing.

To create his fake, he used two known portraits in order to make but one, thus obtaining a new painting that Rembrandt could have painted.

Cleverly placed, the head – while rather small – could have been held by the hand that remains somewhat transparent (portrait in the Cincinnati Museum).

To create the new aspects, the choice of the clothing was that of the Wallcraf Museum, less restrictive than the first portrait (Cincinnati Museum). Again, the painter could use certain aspects of the clothes of the martyr in the under-layers.

We can deduce that our artist had a good understanding of Rembrandt self-portraits! We know that real forgers carry out meticulous studies, even of the drawings of the copied artist!

If the forger’s muse had been present, we would have had a transitional work in respect of the technique: a somewhat smooth, reworked, head supported by vigorously brushed clothing. However, the juxtaposition of the two methods of painting requires talent! It is practically impossible to rival the vigorous manner used by the master painter found in the Cologne portrait that nevertheless appears simple!

|

| 5 – Self-protrait, Wallcraf Richartz, Cologne Museum |

|

| 6 – Probes carried out on the painting |

|

| 7 – Near total removal where the head of Rembrandt is superimposed over the hand of Saint Basil |

|

| 8 – Saint Basil |