In this article, the author discusses ‘glues’, a significant element of the fabrication and preservation in gilding and cabinetmaking. He first explains the virtues of ancient glues such as rabbit skin glue (which is becoming popular again), fish glue (mainly used for Boulle inlays that do not exist anymore), the ephemeral success of synthetic glues (standard Araldite, neoprene contact glue, vinyl glue) and finishes with the comment that, currently, the best solution is a strong glue made from protein fibres extracted from the bones and nerves of cows.

Revue Experts n°9 – 09/1990 © Revue Experts

Through a presentation of the various glues used for gilding and in cabinetmaking, in particular rabbit skin glue, is evoked the drama that woodworkers and gilders are faced with on a daily basis: the deterioration in of the quality of basic products to the extent that they are unable to produce work that is satisfactory. The following study is, therefore, important, not only because when an object is the subject of admiration, it needs to be understood, observed and its life discovered through its fabrication but also because, if we are not careful, the traditional artistic trades that have made France so well known will disappear under a cloud of general indifference.

The tradesmen and artists who work with traditional materials are incessantly subject to modern world avatars that constantly diminish the quality of products sold.

Over the years, for example, shellac is no longer extracted with the same care and contains more and more impurities. The names remain the same, the base products also, for a large majority of products, but the methods of extraction are more and more rapid and less and less refined. Often, preserving agents are replaced with less costly substitutes if they are not simply removed entirely.

Faced with this fait accompli, restorers can easily become confused. Even a strong glue (comprising nerve glue added to bone glue) no longer glues as it used to! For fish and rabbit glues… the same causes, the same effects!

So what should be done? Abandon the old scribblings and recipes learned in dribs and drabs after many years practise and start again with synthetic products?

Or continue, head down, using only traditional products on which our reputation is based but the poor results of which require us to innovate from morning to night?

Neither of these two solutions are, in fact, constructive: the first because we do not have enough experience of the effects of time on new products; the second because the technician advances with hesitation and risks committing unseen errors.

Each sample taken should, therefore, be examined together with persons who are used to using pre-war or current products and with the manufacturers on a case-by-case basis, and there should be no hesitation in contacting chemists who work for European restoration institutes such as IRPA, ICCROM or IFROA(1).

Professional unions and associations, whose principal concern should be the protection of the quality of products used, are too often dissipated by internal quarrels and their horizons sometimes appear to be limited to collecting membership fees.

The French section of the IIC (International Institute of Conservation), a worldwide association, proposes to resolve this type of problem but it does not have sufficient funds, so its resources and actions are limited.

| (1) IRPA: Belgian Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Parc du Cinquantenaire, Brussels, Belgium.ICCROM: International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property, 13 Via di San Michele, Rome, Italy.

IFROA: French Institute for the Restoration of Works of Art, Rue Berbier-du-Metz, Paris. |

Why animal glues ?

Skin, bones and nerves contain collagens that are used in gelatines, cosmetics, the food industry and in glues.

The protein fibres contained in the bones, nerves or skin have the capacity to:

– separate when combined with hot water,

– form a flexible gelatine when water is added and the temperature falls below 20°C,

– bind to themselves and other organic bodies through hydrogen bonding where a water molecule in a bridging point evaporates either due to molecular attraction to the base support, as is the case with wood, or by capillary aspiration, as is the case with the porous substances (chalk, soft plaster) that constitute the preparatory layers for the gilding of wood.

A strong glue that is less reliable

The bone protein fibres mixed with those from nerves results in a glue that is flexible but very hard and even brittle if the bone percentage is too high. “Nevers glue”, the production of which ended more than 30 years ago, was the most sought after by woodworkers. Delivered in brown panes approximately one centimetre thick, it was as transparent as glass, which was the proof of a perfect preparation.

The traditional copper bain-marie is still used in the corner of woodworker or restorer workshops to keep the glue at the right temperature (approximately 60°C). But the adherence of the collagens is mediocre and placing veneers with a hammer becomes more difficult. The restorer is less and less confident in the reliability of his work and unfortunate surprises can occur either when applying the veneer or several months later, when the humidity in the item has stabilised. While several years ago it was still easy to blame the woodworker when blisters appeared under the veneer, it is nowadays preferable to express a judgment that is considerable more circumspect.

In light of such risks, the producers of furniture only use synthetic glues, which are more solid but are irreversible.

Reversibility when restoring

The problem of reversibility when restoring is a critical issue that, in principle, restorers cannot avoid.

More precisely, should a poor quality but reversible glue be used or a good quality but irreversible glue?

The restorer risks less immediate problems using the second but, when the glue ages and has become brittle, the veneer risks falling off and scraping will be required down to the base level in order to carry out the restoration. In the first situation, however, all that needs to be done is to heat the veneer with a damp cloth in order to soften the strong glue and delicately remove the veneer in order to restore it!

The problem therefore remains the quality of traditional glues. At all costs, an attempt should be made to reproduce the good protein glues, as they are currently the only glues that are easily reversible, even after more than 200 years! Rabbit skin glue is the classic example.

THE DEGENERATION AND RENAISSANCE OF RABBIT SKIN GLUE

Since several years, the quality of rabbit skin glue used by, among others, gilders of wood, has constantly diminished. The blocks sold in May 1988 were of such poor quality that the situation had become catastrophic. The glue, prepared with gelatine, decayed the following day, the white glue not being able to be kept for more than two days and breaking down into a fine powder once it had dried.

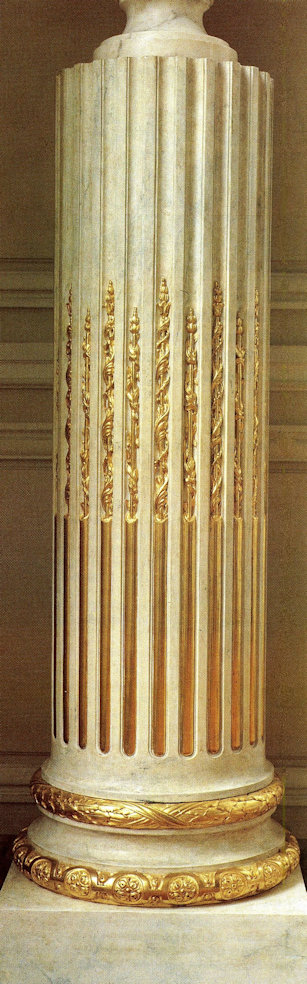

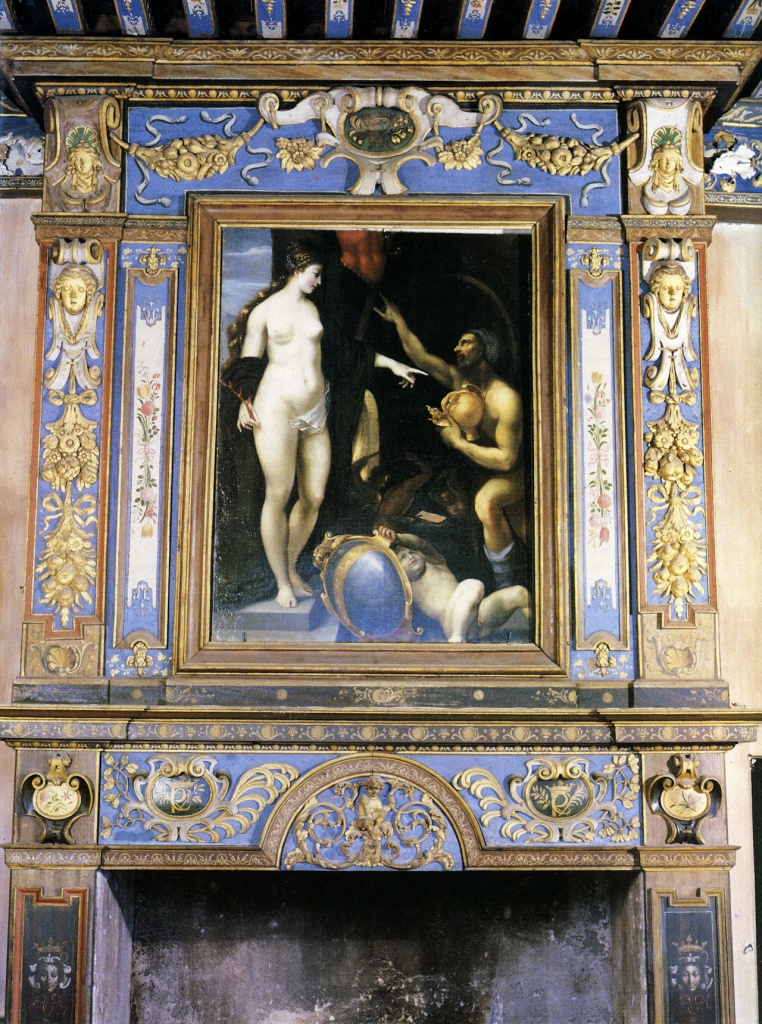

This happened to us when we were working on mouldings for the alcove in the bedroom of Louis XV at the Palace of Versailles, work that should not have any weaknesses and the longevity of which must be ensured for more than 100 years.

Only one producer in Europe

We needed to a solution quickly. I started by seeking out the contact details for all of the glue’s producers. After numerous telephone calls, I ended up discovering that there was only one producer in Europe and that all of the others who claimed to have the same quality were in fact only retailers.

The company that produced rabbit skin glue, among other things, was Etablissements Georges Alquier, situated a hundred or so kilometres from Toulouse.

After the last war, two producers of rabbit skin existed in France, Maison Totin Frères and Maison Chardin.

The visit to the factory

A visit to the factory was necessary. Certain customers with a delicate sense of smell complain about the odour in workshops where a plate of glue is heating in a bain-marie… I could imagine them here, where several tonnes of skins, cut into fine strips, suffer the assault of the sun, flies and vermin: difficult to find the words to describe the smell of decay and decomposition!

The owners, Bernard and Michel Alquier, showed me around all of the sections of the factory without hiding anything and admitted to me that they were considering stopping the production of rabbit skin glue, the market having considerably reduced. The numbers spoke for themselves: 165 tonnes in 1968, 53 tonnes in 1987! This impressive drop was due to professionals in the modern furniture industry turning to synthetic products for their varnishes and plasterers who preferred atomised skin glues extracted from ovine and bovine skins that have been lime washed (the primary production of the Etablissements Georges Alquier, plaster mixed with skin glue, is spread more easily, sticks better to the paint, is slower to harden but becomes harder when dry).

Preparation of the skins

Long past is the time when skin collectors scoured the countryside to provision glue manufacturers. Nowadays, the skins arrive at the factory cut into fine strips, their fur having been removed mechanically. The suppliers are only a few factories specialising in the recycling of rabbit fur for the textile industry. The rabbits come from intensive rabbit farms, stuffed into cages that have never eaten or even seen the slightest blade of grass.

A subsequent degeneration in the glue became apparent in the 1950s. The thin strips had not been lime washed, as the whole skins had been, in order to remove the fur, and the glue contained a high percentage of fur that varied according to the quality of the filtering.

The extraction of the gelatine

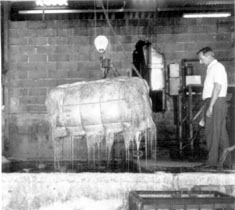

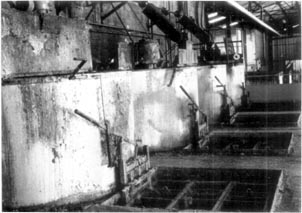

The bales of skin strips are successively placed in four large tanks filled with hot water, the temperature in the first of which is 60°C and the last, 80°C. Each dipping lasts one hour. The ‘juice’ from the first tank has the most collagen and, clearly, is the best quality. The other ‘juices’ are increasing weak in collagen and the temperature must be increased in order to extract it, at the risk of changing the nature of the fibres.

The four ‘juices’ are then combined, filtered with a sieve and sent to a drier that reduces the proportion of water from 50% to 20%. The gelatine is then poured into mould of 1 m x 2 m x 0.30 m thickness that, after cooling, forms large slabs of flexible glue. The slabs are then cut into blocks then tablets. All that remains is to place the flexible tablets onto a grill frame and place them in the long, wind-assisted, drying corridor at 36°C where they take their definitive form. The tablets taken from the surface and the bottom of the slab contain more impurities than the others and are sent to grinding machines to produce rabbit skin glue in powder form.

The use of rabbit skin glue in gilding wood

The dried tablets are sold but cannot be used in such form. They must be diluted by 90% in a volume of water heated to 60°C in order to form a gelatine that can be used. Obviously, that percentage varies nowadays, depending on variations in the glue itself.

Due to some gilders complaining recently that the glue irritated the inside of their mouth when they prepared it, the manufacturer reduced the level of added phenol by one-half. This reduction in the preservation agent modifies the time that the glue can be kept in a gelatinous form (ready for use), meaning that, at the end of a day in summer, it can be thrown away.

Refining and testing a new rabbit skin glue

At the time of my visit, Messrs Alquier reassured me that they were about to attempt to produce a new glue with exceptional qualities. The research for the product, carried out with help from IDETH(2), showed that it was necessary for the manufacturer to be in contact with users of the product. We therefore undertook numerous tests on samples that sometimes went back more than forty years. The tests speak for themselves. (see the table below).

| (2) French Institute for Technical Studies and History of Works of Art, 11 Rue Saint-Simon,Versailles |

|

Engler viscosity

10% concentration |

Bloom gel strength test

|

|

| Chardin glue from 1983 |

1,9

|

380

|

| Chardin glue from 1988 |

1,8

|

300

|

| New glue in October 1988 |

2

|

400

|

THE FABRICATION OF RABBIT SKIN GLUE

This new glue is extracted using four distillation processes at 60°C from selected thin strips. The best skins produced on an industrial scale come from Limousin, but are clearly more expensive than those from Spain or Latin America, which do not have the same level of flexibility. The filtering is also improved by 50 microns to give this new glue its current qualities that were normal yesterday but now are exceptional. Particular care is taken at each stage of the process, such as the skimming and protection of the gelatine from dust. Each plate is now stamped to avoid any confusion or fraud.

FISH GLUE AND MARQUETERY

When André-Charles Boulle developed the technique of inlaying furniture with tortoise shell, he was very quickly confronted with the problem of preserving his works. The sources of materials that he used did not simplify his task: on one hand, the metal used in thread form or as an outline and, on the other, the tortoise shell, bovine horn, ivory, bone and wood did not react in the same manner to ambient variations in heat and humidity.

Wood, for example, expands in the presence of humidity (relative air humidity) and contracts in the presence of dry air. Brass or tin used in marquetry expands only when heated and contracts when the temperature reduces.

‘Boulle marquetry’, when placed in hot, dry, air works in a contrasting manner: the core and wood veneer contracts while the metal marquetry dilates and sometimes comes out of its setting.

The absorbing element in marquetry movement: the glue

The glue produced to maintain these unstable elements must not only stick them to the base using hydrogen bonding to bind them to organic materials but also be very flexible and thick enough to be a separating layer that absorbs some of the dimensional variations in the various elements of the object.

Collagen appears to be predisposed for such task but, because not all collagens have the same properties, a selection is required. Collagen extracted from rabbit skin or, formerly, sheepskin, forms a film that is too thin to carry out this task. That extracted from the bones or nerves of bovines, still used in woodworking for wood veneers, forms a film that is sufficiently thick but that becomes too rigid and rapidly breaks.

An ideal raw material that, no longer exists

This delicate problem was partially resolved (the sons and grandsons of André-Charles Boulle continuously restored the works of their ancestor) by using fish glue. But not just any fish or any part of the fish. The fish in question was the sturgeon and, more specifically, its swim bladder.

The swim bladder of the sturgeon is a membrane that dilates or retracts during the life of the fish. The protein collagen fibres that it is made of have the particularity of being extremely flexible. The glue is extracted using the same process as is used for other protein glues.

The glue from the swim bladder forms an elastic joint that never completely hardens. This fish glue no longer exists nowadays and those that can be found for sale are extracted from the heads, skins and bones of fish without any discrimination between species. The raw material is factory preserved and frozen. There is a huge gap between fish glue from the 18th century and current fish glue, as their properties can attest. The new glue can no longer be used for Boulle marquetry and restorers must use other glues.

THE EPHEMERAL SUCCESS OF SYNTHETIC GLUES

Numerous attempts have been made since the invention of synthetic glues to refine them for the requirements of restorers. Those that have been the most successful are slow-hardening Araldite, semi-contact neoprene glues and vinyl glues.

Standard Araldite

Standard Araldite is a slow-hardening epoxy resin, made by combining two liquids, that forms a film that can be very thick and relatively flexible. Adhesion to metals is very good due to molecular binding, good with wood due to the physical binding with vessels and pores, average with shell and horn. This sufficiently satisfactory result from the standard Araldite led to an enormous success until the first inconveniences appeared ten years later in the 1970s.

Humidity that is permanently found in wood migrates to the surface when the air is dry. Not being able to traverse the film of glue, it is concentrated against the skin of the glue and sometimes leads to water condensation. The moisture that develops then provokes internal damage that materialises in the wood rotting.

Marquetry bound with Araldite becomes unstuck from its base and the restorer must physically remove the resin. Due to the thickness of the glue, this is an extremely delicate process and takes a considerable amount of time. The aging of the epoxy is also a problem because the exact mix of the two components is often difficult to gauge due to their packaging. The glue does not, therefore, attain its optimal qualities and becomes more fragile.

The irreversibility of the epoxy resin on the wood also poses a problem. For example, how can a chair the joints of which are completely filled with Araldite be restored? If the resin is removed from the wood, the joints no longer hold together. But, as the resin is forms a block, the joints cannot be opened at the risk of breaking.

For all of these reasons, this epoxy resin is currently banned from all restoration work.

Semi-contact neoprene glues

Neoprene glues form fine, very flexible, but relatively weak binding films on damaged or fragile wood. Despite good immediate results, they age rapidly and their irreversibility also excludes their use in any restoration work. The same does not apply in modern industry, where they are very popular because the materials used are new, clean and the criteria of longevity and reversibility are clearly different.

Vinyl glue

Vinyl glue, commonly called ‘white glue’ is an emulsion of polyvinyl acetate in water. It has a milky appearance, like all aqueous emulsions.

Appearing just after the Second World War, it has various current variants in drying time and glues both wood and textiles.

Vinyl glue for wood attaches both molecularly and physically to the item without any film. The gluing occurs under pressure to eliminate the forming of a film of glue that would harden and form a weak area.

The surfaces must be in contact, smooth and clean in order to obtain the best result. The glue is widely used in the wooden furniture industry. But in restoration work, where the surfaces are never perfectly in contact or the pressure may generate additional damage, as is the case with borer-filled wood, the white glue must be used with care. Its reversibility on the application of water is not always physically possible.

THE BEST SOLUTION: STRONG GLUE

Strong glue used by cabinetmakers is comprised of protein fibres extracted from bovine bones and nerves using a process that is similar to that of the extraction of skin glues.

The amount of care applied when preparing the panes also plays an essential role in the quality of the finished product. The quality of current products is not the same as the quality of products thirty years ago.

Restorers mix the bone and nerve glues themselves in order to obtain the optimal result to be applied to Boulle marquetry. It would appear (from the frequency of use by restorers) that results similar to those obtained from using swim bladders from sturgeons were obtained in the 19th century. Nowadays, the quality of this strong glue is not the same, but it still appears to be the best glue for Boulle marquetry, replacing the fish skin glue previously used.

The chemical adhesion is mediocre with metal but is offset by the application of an active surface agent such as garlic and increased by a physical bonding to numerous grooves scratched into the metal surface.

Two things strike me as abnormal. The first is that there is still no protective label guaranteeing the stability and origin of the components of the products used by cabinetmakers, gilders and art restorers. The second is that no gilder or institute has tackled the problem at its source by contacting the manufacturer.