Using three specific examples, the author retraces the history of stamps, including their counterfeits and detection. We also discover the Jasmin stamps, a commode by Bernard van Risen Burgh that is unfortunately in the United States and another Riesener that was able to be brought back from London to Versailles.

La revue Experts n° 55 – 06/2002 © Revue Experts

Article 36 of the ‘new’ Community of Joiners and Cabinetmakers Law of 1743, in force only in 1751, provided that “each master cabinetmaker will be required to have his own specific mark and the Community its own mark, (…) and the said master cabinetmakers cannot produce any work, except those working on buildings1, without having first added their mark…”.

This obligation, which was neither a means of advertising or receiving taxes, was not novel. It succeeded the Law of 1467, which itself followed an order of the Paris Parliament of December 1637 that was rarely applied. The affixing of the mark by each master cabinetmaker enabled the quality of the furniture offered for sale by upholsterers to be verified. Independent workers were thus excluded from such sales. According to Bill Pallot2: “The primary reason for the stamp arose from the desire by the Community of Joiners and Cabinetmakers to control the work and prevent counterfeits by independent workers”. The JME mark, used by sworn joiners and cabinetmakers, was affixed in the master craftsman’s workshop by the sworn joiners during four annual inspections. From 1743, the rule was strictly applied, with any master craftsman who breached it risking “confiscation and a twenty pound fine per unmarked item”. It was only abolished at the time of the Revolution.

1.Real or false stamps ?

1.1. The stamping technique

A judgment of 3 August 1761 relates the discovery by sworn craftsmen of false stamps used by upholsterers who had wanted to save money. False stamps do not, therefore, date back to the 19th and 20th centuries.

It would be pointless to today attempt to find the very rare frauds, which were carried out using the same technique, at the same era and had the same patina.

The stamps of the master craftsmen, corporations and well-known workshops were applied using toughened iron stamps, hand hewn from one block. They were very expensive but were used over many decades.

Each stamp was, therefore, unique, whether due to its size, the characters used, the layout or positioning of the letters.

Commode… Louis XIV era ‘by Jasmin’. Sale on 10 December 1973 in the Galliera Palace, Paris. Sale on 9 December 1981 at the Georges V Hotel, Paris.

1.2. Counterfeit stamps

From the beginning of the 20th century, counterfeiters tried to create false stamps using traditional irons, such as the famous Maillefer that inundated the first part of this century with very high quality, stamped, copies. Other counterfeiters, from the Second World War through to 1965, used ‘irons’ cut from very hard wood such as ebony to reduced cost of the counterfeiting. Despite the skills of the engraver, the trace left by such templates, which were thicker and not as sharp as those made with iron, and had a softer, less defined, aspect. The template, often made of wood, was used only one to five times.

From 1965, very high performance synthetic resins began to be used. The elastomeric resins enabled mouldings to be taken to micron precision and were used to take imprints of the stamps. Then, using electroplating, the falsifier produced a reproduction of the ‘iron’ in copper. Or, a resin with very high mechanical resistance and very low contraction properties was directly poured into the mould.

The false stamps that resulted from these new moulding processes exactly reproduced the original mark and require careful analysis in order to be detected. The detection of such modern counterfeits is possible only with the aid of a microscope. An expert will examine the manner in which the wood fibres are crushed, whether corners have been naturally oxidized and whether the patina has a natural appearance (wax, varnish, grease, etc).

This optical microscope examination is accompanied by photographs, which is an excellent form of proof.

Commode… Louis XIV era … ‘attributed to Jasmin’ ‘Louis XIV era’ sale on 27 May 1987 in Monaco.

2. The art market and the stamp

While the stamp attested to the quality of the seats and furniture at the time of their fabrication, today it guarantees the origin of the furniture. Between two items of furniture of equal quality, one bearing the mark of the cabinetmaker and the other not, the second will have an increased value depending on how well known the signatory is. But the quality of the item also counts in its value. Two commodes, both stamped by the same cabinetmaker, will not draw the same bids depending on the quality and the richness of their respective decoration.

2.1. A false but adequate stamp

A false stamp provides an item of furniture with an increased value only to the extent of that of the reputation of the master craftsman! In order to do so, it must correspond to his production: the works of chair makers such as Jacob, Tilliard or Séné have distinctive qualities of a particular type. The same applies to cabinetmakers, the Riesener style being as different to the Cressent style as that of Vandercruse Lacroix. The affixing of a stamp on an item of furniture the style of which does not correspond to that of the master craftsman does not add much in the way of increased value. The counterfeiter is required to be erudite in the subject matter and add the appropriate stamp…

The second half of the 20th century witnessed numerous well-documented publications on the subject, initiated in particular by Count François de Salverte and Pierre Verlet. These two famous historians opened the art market to master cabinetmakers and Crown furniture. They were followed by

B. Pallot3, J. D. Augarde and J.N. Ronfort4.

‘Mazarin desk in veneered wood … attributed to Jasmin’

‘Louis XIV era’ sale on 27 May 1987 in Monaco.

2.2. An entirely invented stamp and cabinetmarker

The flower-inlay furniture by Jasmin.

Similar quality furniture that was stamped being coveted, certain people involved in the art market had the idea of inventing stamps. For example, furniture covered with Dutch inlays of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century were from 1965 to 1980, attributed to a cabinetmaker invented for the purpose. Connoisseurs identify such furniture by the small jasmine flowers finely encrusted in ivory in the exotic wood panels, with large foliage and flowers. The facts proven in True/False5 can be summarised as follows: the art market expanded from 1965, such that quality items came onto the market, with commodes and Mazarin desks finding buyers at significant sums. The sales catalogues helped raise bids. Superlatives such as “very pretty inlay with ornate jasmine flowers”, “superb production”, “very rare” or “of exceptional quality” were rapidly overused, such furniture becoming “in the Jasmin style”, then “by Jasmin’s entourage”, “from the Jasmin production” and, as a logical consecration, “stamped by the cabinetmaker Jasmin”. The value of such furniture increased as the fictive cabinetmaker became increasingly well known. The article cited above, illustrated solely by photographs from sales catalogues and their captions, ended the ephemeral life of the master craftsman. The Netherlands, where stamps were infrequently used, rediscovered its orphans as stamps were no longer able to be applied.

This anecdote provokes the following thought: how could the mark from a very recent stamp be above any suspicion? How could such a fraud still be possible in our era?

I think that where the object is above suspicion, ie, it comes from the era stated, the stamp does not raise any particular suspicions.

This is very different in the context of a court-ordered expert report where the expert cannot commit any errors and employs, if necessary, all current means at his disposal to produce a rigorous report with supporting proof on any modifications made to an item of furniture.

In auctions, on the other hand, the omnipresent vagueness is part of the sale, from the permanent search for the bargain that the purchaser hopes to make to the detriment of the seller, who is backed by the knowledge of the expert and the auctioneer.

Commode by the Dauphine in Japanese lacquer produced by the cabinetmaker Bernard Van Risen Burgh (B.V.R.B.)

Commode in the Louis XVI library in the Versailles Palace.

2.3. The changeable value of an exceptional item of furniture

One of the most beautiful commodes in the world.

The case of the commode6 stamped by the cabinetmaker Bernard van Risen Burgh is even more edifying on the development of knowledge after the war, the professionalism of those in the art market and the importance not only of stamps but also any type of mark.

On 15 March 1973, the estate of Mrs Henry Farman was put up for auction by the firm of Ader Picard Tajan at the Galliera Palace, including “a commode in old Japanese lacquer, stamped BVRB, Louis XV era, Josse collection, May 1894. Experts: Messrs J. and J. Lacoste”.

In May 1894, those initials, of one of the principal cabinetmakers for King Louis XV, had not yet been identified. The merchants7 supplying the court having little benefit in advertising their subcontractors, it was not until research was carried out by François de Saverte then Pierre Verlet and, lastly, a pupil of the latter, J.P. Baroli, that the identity of the cabinetmaker who had hidden behind those four initials was discovered in 1959!

On 15 March 1973, Bernard van Risen Burgh had, therefore, been identified for 14 years and was already acknowledged as being one of the most important cabinetmakers of his time. In the caption, the sale experts stated that a similar commode belonged to her Majesty the Queen of England; it was subsequently discovered that seven variations existed. The estimate of 550,000 francs was pulverized and exceeded one million francs. The audacious Parisian antique dealer who topped the bidding presented a photograph of it in the prestigious review L’Œil in May 1981 with the sole caption: “One of the most beautiful commodes in the world, Louis XV era, in old Japanese lacquer, stamped BVRB”, with no other information in the advertisement. A buyer was found, a New York dealer, who exported it to the United States without any difficulty. The dealer presented on the American market then provided his stock, including the commode, to the Christie’s auction house in 1998. The French furniture expert Patrick Leperlier realized that the inventory number on the rear crosspiece corresponded to a royal furniture number. The BVRB commode was not only one of the most beautiful commodes in the world but became the commode that was delivered on 23 January 1745 to the Versailles Palace by the upholsterer Hebert for the bedroom of the Dauphine, Marie-Thérèse-Rafaëlle, daughter of Philippe V of Spain, on the occasion of her marriage to the oldest son of Louis XV.

This happy discovery raised the range of the estimated value from 22 to 34 million francs. However, very contradictory information circulated prior to the sale of 24 November 1998 on the authenticity of the inked inventory number: no purchaser was therefore found for the commode. This anecdote illustrates the changeable nature of the value of an exceptional piece.

Detail of the gilded bronze decoration on the central drawer. Commode in the Louis XVI library at the Versailles Palace.

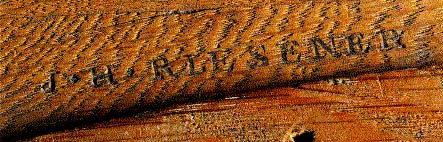

Stamp by J.H. Riesener.

2.4. A Commode in its place

The French commode the most expensive in the world.

Out of prudence, the estimated value of the commode was placed at between 15 and 25 million de francs. It was adjudged at 77 million francs! Due to the combined efforts of the French State, the Friends of Versailles Association, the Versailles Foundation and Mrs Pinault, this work by Riesener8 has since reintegrated its original place.

What expert could have foreseen such success…after the preceding disappointment?

If, nowadays, historians have carried out remarkable studies on French cabinetmakers of the 18th century by identifying productions, stamps and customers, experts still need to constantly verify the authenticity of the items of furniture, their bronze trimmings, inlaid or lacquered decoration, marks and stamps. Modern-day furniture is easily valued according to its interest and condition.

As to providing a precise estimate of the value of an exceptional item, the expert does not have a crystal ball…

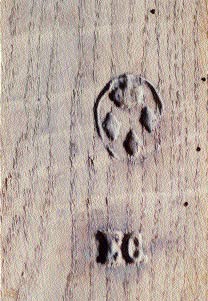

Iron marks: the three fleur-de-lis and the crown in the oval indicate a royal domain; the letters ‘E.C.’ correspond to Ecuries de Compiègne.

Iron mark from the B.V.R.B. stamp

Inscription on the upper crosspiece behind the commode featuring the inventory number of the Versailles Palace. Analysed in London at the French Museums Laboratory, the ink is identical to that taken from other items of royal furniture. Idem for the graphism of the characters.

NOTES

| 1. | Relating to woodwork, staircases, roofing, etc. |

| 2. | B. Pallot, L’Art du siège au XVIIe siècle, Editors ACR Gismondi. |

| 3. | Specialist in chairs. |

| 4. | Cabinetmaker specialists. |

| 5. | Work published by Editions Faton in 1994. |

| 6. | The editors thank Mr Patrick Leperlier for having authorized the publication of the photographs of the two commodes. Christie’s photos. |

| 7. | Their modern-day equivalent being interior decorators. |

| 8. | German by birth, J.-H. Riesener joined the Oeben workshop in Paris. He finished the cylindrical desk for King Louis XV on the death of his employer, then took over the workshop and married the widow. His productions, of modern taste, rich and elegant, pleased Queen Marie-Antoinette, who made him her favourite supplier. |