The author analyses the concepts of the originality of a sculpture from technical, stylistic and tax points of view. Since the legal provisions enacted in 1968 and 1981, the production of original copies is restricted in France to eight copies made from the same mould, to which can be added four copies known as “non-commercial” artist’s copies. Prior to that constraint, the production of original editions was unlimited. Gilles Perrault gives us an update on this unique aspect of French sculptures.

Article from Revue Experts n° 85, Août 2009 © Revue Experts

A reading of sculpture exhibition and auction catalogues often leaves us perplexed as to whether the work in bronze, plaster or terracotta is unique, original, an original edition, a limited or unlimited edition or a copy. The notion of originality is clearly easier to understand when dealing with a painting, which is inherently unique. A workshop copy or copy produced by another artist in some other era is considered to be a reproduction. Only the painting produced by the master painter can be the original. Workshop reproductions then raise the issue of attribution: which student did the work and what part of the work was done by the master, who sometimes even signs?…

A painting, even though unique, may also not be original. This means, obviously, that the work lacks original creativity and that its author stayed within a well-established style. The subtlety of the word ‘original’ can be understood when attributed to a person, marking a difference and highlighting its rarity within a group of paintings. When used in reference to a painting, it indicates that we are confronted with a first work created by the master painter and with his retouching, stylistic evolution, it thus being ‘an original work’ differentiated from others. It is, therefore, so clear that it is unique that this is nearly never referred to in relation to paintings.

1. ANTIQUES

Conversely, very few sculptures remain unique. Since ancient times, a statue that has attained a certain success was destined to be reproduced in numerous models, either through copying or by the use of moulds. Rich Romans passed their orders for bronze or marble sculptures by choosing models moulded from plaster from the Greek originals in workshops across the peninsula. More or less faithful copies, sometimes with significant variations, nonetheless constitute, in the view of art amateurs, original works of art, in both meanings of the word, even though the sculptor is rarely identified and it is not known how many copies were produced in the numerous workshops.

The patina of the centuries, adding its mark, also confers an originality to each sculpture. These copies were hand-sculpted in marble or clay for the bronze copies. Such that, for each copy, a new sculpture produced by the hands of an artist is very rarely simply a cast reproduction: it is, therefore, technically an original work. The vicissitudes of war and other unexpected events decimated this abundant production, rendering such sculptures extremely precious today.

2. FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE 18th CENTURY

2.1. Back to Antiquity

In this artistic era, called the Renaissance, lived a number of master painters and sculptors who created works for well-known personalities. The need to multiply the works through the moulding process became necessary in order to satisfy demand. The high interest in antiques gave rise to numerous copies of the same subject matter in various dimensions and using various materials such as marble, bronze, terracotta and plaster. The discovery of tombs richly decorated in frescos and sculptured details (grotesque) was so popular that, for two centuries, all artists sought to reproduce countless works and transpose them into the decor of European palaces. These copies remain, nonetheless, ‘original works’.

2.2. The impact of royal taste

The principal purpose of young French artists staying in Italy or at the royal academy in Rome was to copy antiques. The most successful works were returned in order to decorate royal palaces. After their classics, these artists, experienced in making copies, were able to create their own works according to ‘French taste’ or, rather, the King’s taste. Louis 16th, well advised by artists such as Le Brun and Girardon, led the way in freeing them from their early years by unifying production in a baroque style devoid of excessive embellishments.

1. Louis le Grand, by Bernini. Original in marble protected from vandals in the King’s large stables at Versailles.

The details in the equestrian sculpture by Bernini, also know as ‘Le Bernin’, reflect the impact of royal taste. Louis the Great did not let himself be influenced by the aura of the Italian master sculptors of his era. He had François Girardon reproduce the work that the latter had made representing him on horseback, in a large-scale in marble, because he considered its volutes, curves and counter-curves to be too excessive. Even with its details toned down by the French artist, the work, considered to be too tormented, did not find favour with the King, who installed it far from sight at the end of the Swiss lake in the Versailles Park.

This original work – in several aspects, because it is unique and created by two artists – was duplicated in marble-powdered resin in the early 1980s in order to create an imitation marble mould and replace it at the end of the park in order to avoid it being a target for taggers. Then a second copy in lead was made in 1988 to decorate the Pyramid courtyard in the Louvre in Paris (photos nos. 1 and 2).

2. Louis le Grand, by Bernini. Lead mould decorating the courtyard of the pyramid at the Louvre Museum since 1989.

2. Louis le Grand, by Bernini. Lead mould decorating the courtyard of the pyramid at the Louvre Museum since 1989.

2.3. Uniqueness and originality

These two moulds, created nearly 250 years after the creation of the work and more than 70 years after the death of the two artists, cannot be considered to be original works – this is clear. But if such reproductions had been made when the artists were still alive in a material used at that time such as bronze, lead or plaster, it is clear that the notion of originality would be now raised because the sculptors would certainly have supervised the production, even adding or removing certain details, thus creating a new version. Take, for example, the statue of Leto(1), the mother of Apollo and Diana, produced in marble by the Marsy brothers to decorate a pond in the central alley of the Versailles park (photo no. 3). This original and unique work gave rise to reduced copies in bronze produced shortly after the death of the artists. They are today considered to be originals (photo no. 4).

3. Leto and her Children. The unique original in marble by the Marsy brothers is found in the lake of the same name in the park at the Palace of Versailles. The central group of figures was replaced in the 1980s by a resin mould containing marble powder. The Lycians, metamorphosed into Batracians, are originals, in gold-plated lead.

3. Leto and her Children. The unique original in marble by the Marsy brothers is found in the lake of the same name in the park at the Palace of Versailles. The central group of figures was replaced in the 1980s by a resin mould containing marble powder. The Lycians, metamorphosed into Batracians, are originals, in gold-plated lead.

Leto and her Children.

Leto and her Children.

Smaller-scale bronze, lost-wax cast, circa 1715.

It is, therefore, important to dissociate the notion of uniqueness from that of originality, because a work created in terracotta or marble is unique while an original work in bronze may be the sixth or even the twelfth copy from the same mould.

3. FROM THE 19th TO 20th CENTURIES

3.1. The bronze art fashion

It was in the 19th century, with the emergence of the bourgeoisie eager for recognition, that sculptures multiplied in numerous sizes and materials depending on their success at salons. Wanting to monitor the quality of their works in order that they did not run low in bronze copies, certain sculptors such as Alfred Barye became casters. Following the same path, Emmanuel Frémiet established a good business creating sand-cast copies of his works, selling them directly from his workshop or from French and overseas salons.

Alfred Barye initially numbered his works, before realizing that his customers were reluctant to purchase higher numbered works: he was required, against his wishes, to stop numbering his works in circa 1847.

As a general rule, the new work was presented at salon in its original dimensions in marble or plaster. Then, according to its success, it was reproduced in different materials: bronze, cast iron, plaster, terracotta or marble, in different sizes. The ‘original size’ corresponds to the scale of 1 in creating the work. The processes for reducing or increasing shapes using a three-point compass or a gauge, like for the Colas process, facilitated the development of sculpture copies.

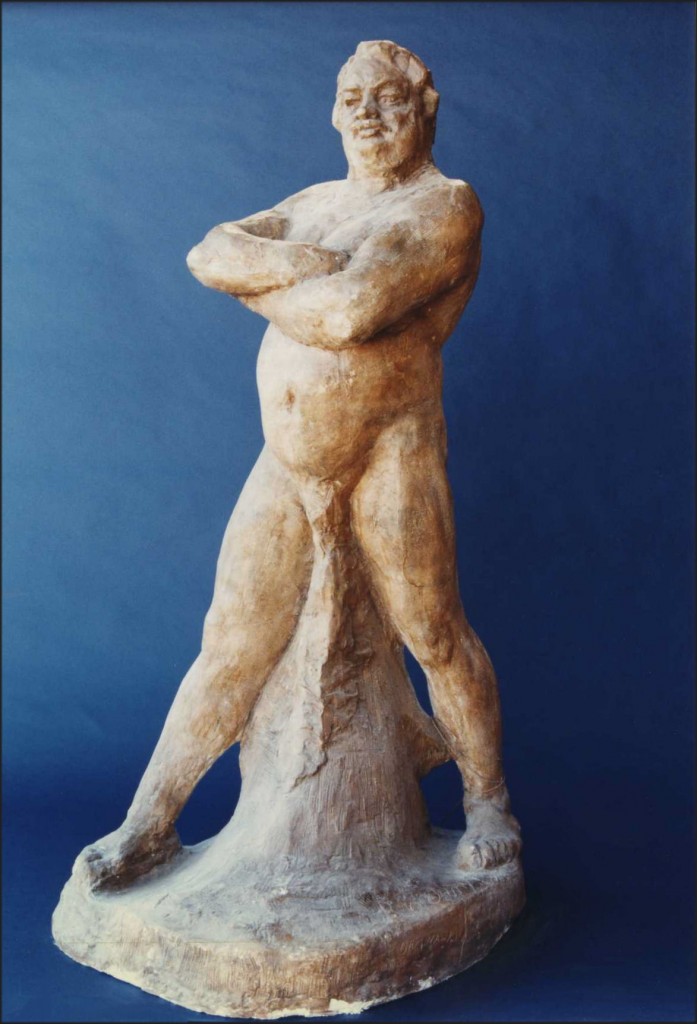

5. Nude Balzac by Auguste Rodin

5. Nude Balzac by Auguste Rodin

Workshop plaster created by the Rodin Museum and given to the Georges Rudier foundry in order to obtain originals in bronze (sand technique).

6. The engraved word ‘original’ on the edge of the base indicates that this is the original scale of the work.

6. The engraved word ‘original’ on the edge of the base indicates that this is the original scale of the work.

7. Joints (left by the multiple-piece mould) visible in lowlight on the surface of this copy confirm that it is a workshop plaster and not a plaster original.

7. Joints (left by the multiple-piece mould) visible in lowlight on the surface of this copy confirm that it is a workshop plaster and not a plaster original.

All sculptors of the 19th century became interested in the world of bronze art because producing a number of copies enable them to multiply their profit and give them more time to create other works. The original was thus the copy produced in the same dimensions as the original in terracotta or wax (photos nos. 5 to 7). It was generally limited only by its success. As previously stated, in addition to this original copy (scale 1), foundry catalogues included half and quarter sizes and enlarged copies (scale 2), etc (Photos 8 to 11). When Auguste Rodin assigned his reproduction rights in The Kiss and The Eternal Spring to Ferdinand Barbedienne, the contract covered different sizes but no limit on the number of copies. In order not to alter the nature of the plaster model and to make a number of casts through the sand mould process, the Barbedienne house created models out of bronze from which, if required could be made hundreds of moulds and copies. The copies made from such ‘master models’ in bronze had the privilege of being of high quality, but were considerably expensive and paid for themselves only after numerous copies had been made.

Apart from several artists such as Mène and Frémiet or the publishing houses such as F. Barbedienne, which used only this process, for the large majority of the other sculptors, the quality of the copies from master models and plaster diminished after the first dozen bronze copies because of the wear and tear on the moulds or plaster models. It can be considered that a plaster model was tempered after a dozen sand moulds and that a plaster and gelatin model used for the lost wax process lost its sharpness after six copies. After such numbers, the founders used a new model.

8. Stock seized during the first G. H. case by the Lure Regional Court, containing, among others, original works and counterfeits of Auguste Rodin, P.J. Mène and the Comte du Passage.

8. Stock seized during the first G. H. case by the Lure Regional Court, containing, among others, original works and counterfeits of Auguste Rodin, P.J. Mène and the Comte du Passage.

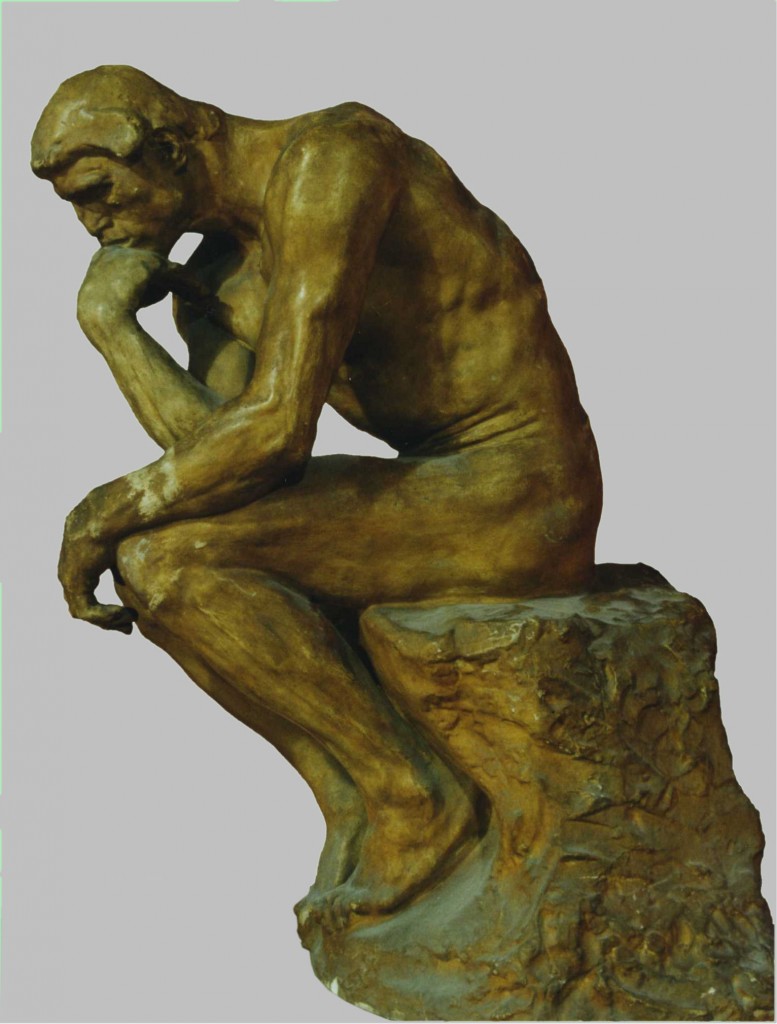

9. The court expert discovered, amongst the stock of 2,500 sealed objects, a workshop plaster of Women Chatting by Camille Claudel. Behind is a large-scaled workshop plaster of The Thinker prepared for sand casting.

9. The court expert discovered, amongst the stock of 2,500 sealed objects, a workshop plaster of Women Chatting by Camille Claudel. Behind is a large-scaled workshop plaster of The Thinker prepared for sand casting.

10. The Thinker, scale 1, by Auguste Rodin, approx. 72 cm high, original dimensions, Rodin Museum. Workshop plaster from the end of the 19th century or beginning of the 20th century that was used to create several original bronze copies. Seven original copies in bronze are recorded as having been cast prior to 1901, to which should be added, from 1902, thirty or so cast by the Alexis Rudier foundry, 11 of which from 1926 to 1945, then eight official copies ordered by the Rodin Museum from Georges Rudier from 1955 to 1969. To these 46 legal copies should be added numerous illegal copies produced with the consent of the successor (the Rodin Museum) and numerous counterfeits made in France and overseas and, finally, reproductions indicated as such where such word engraved in the bronze was not ground off by fraudsters.

10. The Thinker, scale 1, by Auguste Rodin, approx. 72 cm high, original dimensions, Rodin Museum. Workshop plaster from the end of the 19th century or beginning of the 20th century that was used to create several original bronze copies. Seven original copies in bronze are recorded as having been cast prior to 1901, to which should be added, from 1902, thirty or so cast by the Alexis Rudier foundry, 11 of which from 1926 to 1945, then eight official copies ordered by the Rodin Museum from Georges Rudier from 1955 to 1969. To these 46 legal copies should be added numerous illegal copies produced with the consent of the successor (the Rodin Museum) and numerous counterfeits made in France and overseas and, finally, reproductions indicated as such where such word engraved in the bronze was not ground off by fraudsters.

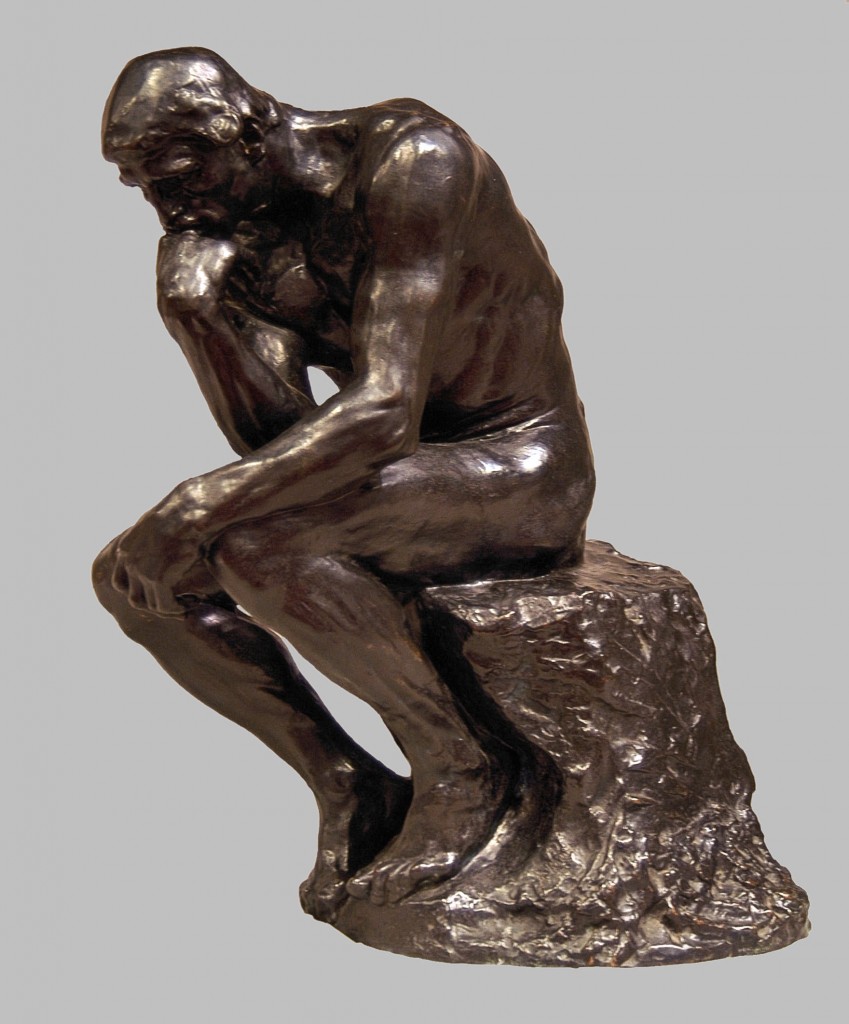

11. The Thinker by Auguste Rodin. Sand cast produced by the Alexis Rudier foundry, scale 1. Copy in bronze, unlimited original, circa 1910, having reached a record auction price of €3.095 million on 17 January 2009 at the Hotel Drouot in Paris thanks to its irreproachable pedigree. Its former owner had bought it in 1917 (experts Brun-Perazzone).

11. The Thinker by Auguste Rodin. Sand cast produced by the Alexis Rudier foundry, scale 1. Copy in bronze, unlimited original, circa 1910, having reached a record auction price of €3.095 million on 17 January 2009 at the Hotel Drouot in Paris thanks to its irreproachable pedigree. Its former owner had bought it in 1917 (experts Brun-Perazzone).

3.2. The tax originality or an original work as seen by the tax authority

The legislature relied on its technical findings to provide, in 1968, a limit to copies considered to be originals in order to determine what VAT rate should be applied to copies(2). Works up to 8 copies, stamped in Arabic numbers, were considered to be originals, subsequent copying was mass production. The first 8 copies then benefited from the reduced 5% VAT rate attributed to artists, compared to the current 19.6%. The legislature then, in the same regime, allowed a supplementary, non-negotiable, 4 copies, known as ‘artists’ copies’ (Administrative VAT documentation, 3-k 213). Artists and foundries rapidly benefited from this extension, marking ‘H.C.’ (non-commercial) or ‘E.A.’ (artist’s copy) followed by a number up to 4 in Roman numbers. The extension led to a number of excesses. The successors did not hesitate to increase the number of works produced by the artist while still alive by producing a post-mortem original copy without taking into account copies produced before 1968.

After the Second World War, to alleviate a lack of clarity in casts produced, the Rodin Museum, as the artist’s successor, had already instituted a limit of 12 copies described as commercial and numbered from 1 to 12, to which it added the number 0 as a reserved copy for its collections. It was only from 1982 that the Rodin Museum followed the line of conduct imposed by Decree 81-255 of 3 March 1981 (3), casting no more than 8 ‘original’, tradable, bronzes numbered from 1/8 to 8/8 and four artist’s copies numbered from I/IV to IV/IV destined for French and foreign cultural institutions, including its own copy.

Other than this Museum, which has been trying for the past 90 years to resolve the issue of the originality of bronzes and at the same time respect the artist’s testament, various fraudsters have produced non-numbered copies, referring to them as trial copies offered by the foundries! Remember that founders, unless clearly stated otherwise, cannot and have never been able to freely use the models that are given to them by the artists. They cannot either commercialize workshop plasters or bronze copies for their own benefit without specific agreement from the artist or his successors.

Original copies, limited to 200 or even considerably more, can be found in other materials than bronze and released with false advertising. Their original aspects are only in the material used or the dimensions. The use of such descriptive often leads the ordinary customer making an error because he thinks that he possesses a rare work. He is also surprised to see works entitled ‘H.C.’ or ‘E.A.’ up for auction. But, certain successors who produce artists’ copies consider that they can offer or even sell them to others who then dispose of them as they wish(4).

12. Wounded Greek soldier (Philocthetes), unique, original, terracotta,

signed before being fired, T. Géricault.

12. Wounded Greek soldier (Philocthetes), unique, original, terracotta,

signed before being fired, T. Géricault.

Produced in only a few minutes, the time for a workshop break, the artist was able to embody the full tragedy of the immobilized soldier, his legs pierced by two arrows.

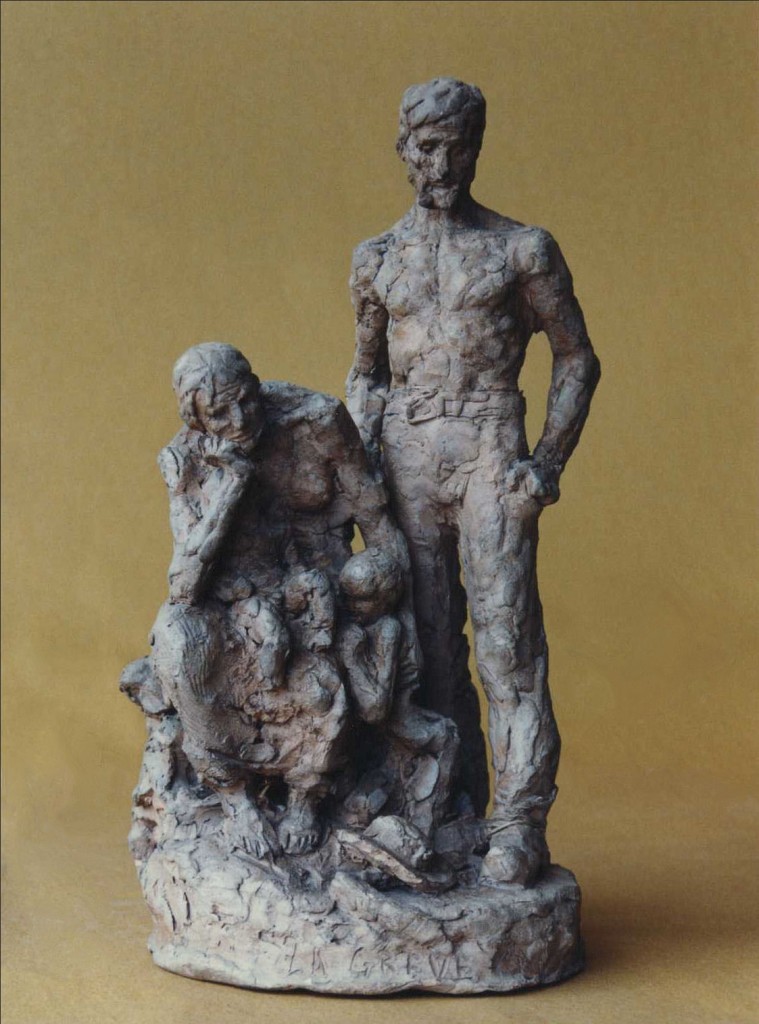

13. A Group of Labourers by Jules Dalou, unique, original, terracotta.

13. A Group of Labourers by Jules Dalou, unique, original, terracotta.

4. THE UNIQUE WORK: THE CREATIVE ACT

With knowledge of the above, we should note that the technical and stylistic originality of a sculptured work is the opposite of the tax concept of originality. The sculptor works the stone, marble, clay, terracotta (grey clay), wax, wood and, from the middle of the 20th century plasticine, self-hardening modeling clay, etc… He produces a unique work with his own hands using materials of his choice, from which arises the concept of stylistic originality in the copy and that of technical originality if the work is entirely copied by hand. (Photos nos. 12 and 13)

Until the middle of the 20th century, grey clay was most common material used to create average-scale and large-scale models. But in order to maintain its plasticity and volume, it had to be constantly kept humid. Wax, which is harder to manipulate, and therefore takes a longer time, is more suitable for small-scale figures and is not as restrictive. Auguste Rodin, Camille Claudel, Bourdelle and many others commonly worked with potters’ clay, which is a flexible material that is easy to work and economical… (Photos nos. 14 to 17). The unique work thus created must be moulded in plaster as rapidly as possible after being completed in order to conserve the full detail of its form and asperity.

4.1. The fully handmade, unique, copy

From a technical point of view, a sculpture, whether invented or a copy, is unique where it is not produced using the overlaying process. A work that is entirely reproduced by hand possesses a certain originality that sometimes differentiates it from its initial model only by tiny details. But, even fully resculpted faithfully or with variations, a copy must be stated to be a reproduction and contain the name of the initial creator. Otherwise, without such indication, the legislature will consider such work to be a counterfeit, even if the author’s rights have fallen into the public domain (70 years after the death of the artist).

4.2. The transposition of the model into marble

Where the material is rigid and unaffected by variations in humidity, the unique work can remain as it is. This is the situation, generally, for statues in stone, marble, wood, etc. Auguste Rodin, who worked nearly entirely in clay, relegated the marble work, which was time-consuming and fastidious, to his numerous assistants. The result being that specialists acknowledge, for example, the hand of F. Pompon in the production of Auguste Rodin’s works in marble, which remain, nonetheless, unique and original works signed by the master sculptor.

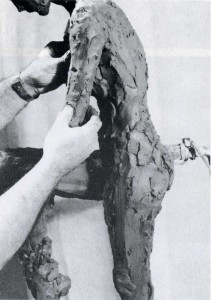

14. Potter’s clay is kneaded onto a metal frame.

14. Potter’s clay is kneaded onto a metal frame.

15. The work in progress is covered with a humid cloth during breaks so that the clay does not retract.

15. The work in progress is covered with a humid cloth during breaks so that the clay does not retract.

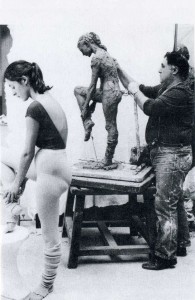

16. The model, the work, the artist in 1988.

16. The model, the work, the artist in 1988.

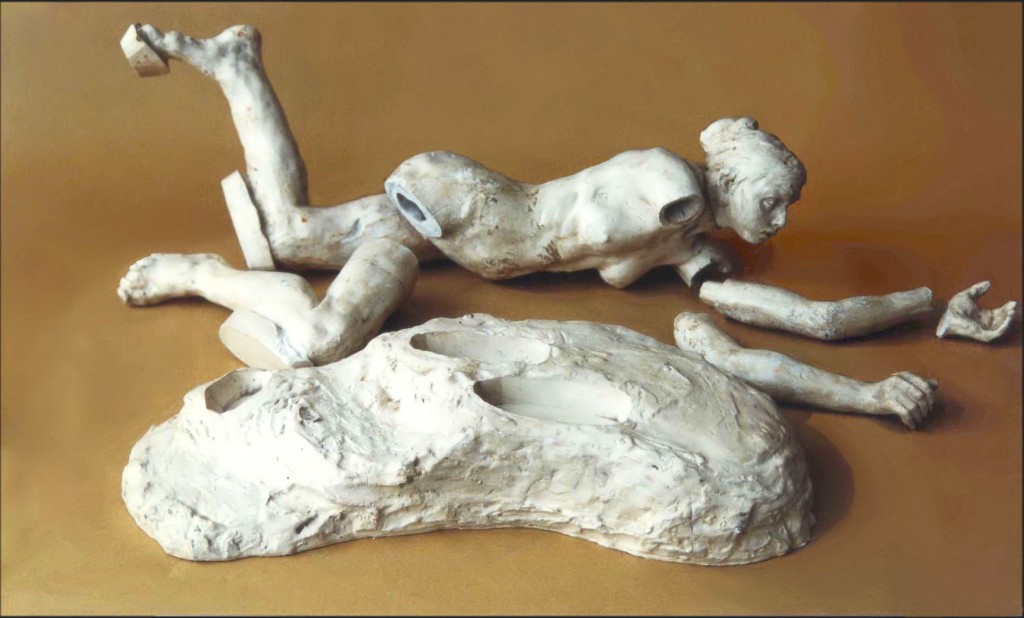

17. The completed work, next step the moulder.

17. The completed work, next step the moulder.

5. FROM CREATION TO CASTING

5.1. The mould in hollow plaster, preserving the creative act

Until the middle of the 20th century, the moulder travelled to the artists’ studios and delicately surrounded the work in an initial, fine, layer of plaster, then a second, thicker, layer, using one or two shells. This mould was called the hollow cast. The clay that gave it its form was then removed in small pieces to enable plaster to be poured into the original mould (in positive). Thus raw works in clay or wax were destroyed, existing only in negative form in the plaster.

5.2. The second creation of the work: the unique plaster original

The ‘hollow’ mould (shape in negative form), cleaned, repositioned, served as a base for the pouring of a unique plaster original that therefore enabled the ‘rebirth’ of the work. Because of numerous counter-angles, removing the mould for this plaster could be carried out only by breaking the hollow mould(6). This plaster original was, therefore, extremely precious yet fragile. It was important to duplicate it in order to protect the creation.

5.3. The preservation of the work by producing duplicates: the multiple-piece mould, workshop moulds or releases

The artist gave only a duplicate in plaster to the founder and carefully held onto the plaster original. So, for reasons of security, the plaster original was duplicated with the aid of a new plaster mould. The latter, created on the plaster original, a solid matter compared with potters’ clay, was made in pieces interlinked between them. They were then dismantled after pouring in the workshop plaster (photos nos. 18 and 19). This, unlike the first, destroyed, mould, enabled more than one plaster copy, called a ‘workshop’ plaster, to be produced. The workshop plaster was either used to make ‘sand’ moulds (copies) for the foundry, in which would be poured molten metal (these copies were always negatives of the work in positive to be copied in bronze) or to enable an adjuster to produce larger scales or reductions in plaster or to transpose the work into marble or stone. Despite being given to a master technician, it remained the property of the sculptor. While often forgotten on a workshop shelf, it reappeared years later after the death of the artist, like a present … The plaster from the multiple-piece mould could also be used for presents or a mass production of the work. In such case, it did not have the marks from being used in a foundry or the fixing of measurement points.

18. The Kiss of the Faune by Jules Dalou

18. The Kiss of the Faune by Jules Dalou

Antique plaster copy, terracotta-style patina, cut to serve as the master model for counterfeiters in circa 1990 ‘original copies’ in bronze.

19. The Implorer, scale 1, by Camille Claudel.

Workshop plaster (from the overlaying process, a copy in bronze by Eugène Blot, produced by counterfeiters) prepared for the production of bronze copies for the sand casting technique.

20. The Implorer by Camille Claudel, ‘large model’ in original scale. Bronze work before patina: counterfeit from preceding plaster (sand technique).

20. The Implorer by Camille Claudel, ‘large model’ in original scale. Bronze work before patina: counterfeit from preceding plaster (sand technique).

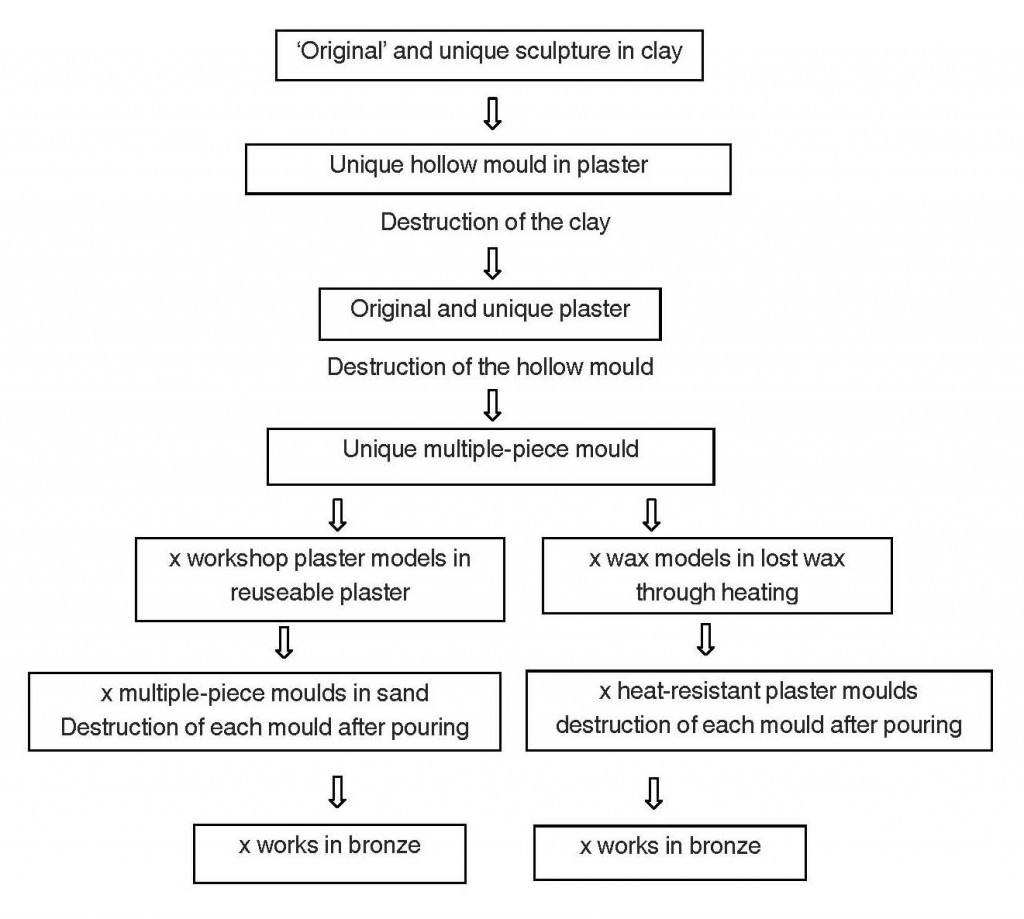

5.4. Casting in bronze

Bronze, initially a copper (min. 65%) and tin alloy, became a generic term that also included brass (copper and zinc alloy). It is a material used, among others, for duplicating forms, but is also chosen because it can be poured and becomes unalterable. (photo no. 20). It takes form, for our purposes, by way of fusion and pouring into a heat-resistant mould. It cannot, under any circumstances, be directly worked by the sculptor. Any bronze statue is, therefore, the result of collaborative work: the work is successively carried out by the moulder, the founder, the engraver and, lastly, the patineur. The bronze copies produced by workers nonetheless kept all of the details of the original work (cf, table of successive phases in the production of a bronze work of art up to the middle of the 20th century). It should be noted that only plaster originals, workshop plasters and multiple-piece moulds can be reused. These successive duplicates cannot, however, be made without altering the initial work, which justifies art amateurs seeking the copy that is closest to the original work produced by the sculptor.

Table of successive phases in the production of a bronze work of art up to the middle of the 20th century

6. THE LAYERING OR MULTIPLICATION OF UNIQUE ORIGINAL WORKS

Rodin is an interesting example because, in addition to his works modeled in clay or wax, the artist habitually transformed an original master in multiple ways, giving rise to secondary original works or new master copies. He would ask his moulder to produce several workshop copies in plaster then change heads, amputate limbs or modify positions. He would even change sizes or group together various subjects.

All of his works, each different from the next, became unique and original. They were in plaster in order to facilitate the cutting, additions and assembly. This process is called ‘layering’.

CONCLUSIONS

An original sculpture in bronze results from various moulding and preparation stages before being presentable and resembling the initial work in clay. It could be unique or in multiple copies or, since 1968, copied 8 times only, with an additional 4 artist’s copies, all retaining the label ‘original work’. The copies made after the death of the artist by his successors, up to the authorized limit, also retained the ‘original work’ description. But these posthumous castings, not supervised by the artist, even though ‘original’, do not have the same value for art amateurs as the copies made by the sculptor when still alive.

A plaster sculpture is considered to be an original where it is produced directly from the hollow mould. This unique plaster original cannot be compared to later copies obtained with the aid of another assembled mould. For enlightened art amateurs, the value of the plaster original comes from the extreme accuracy in the production of later works, while a workshop plaster does not produce all of the details created by the artist.

A terracotta sculpture is considered to be an original where it is a work arising directly from clay; natural clay mixed with ground brick (firesand). The firing significantly modifies the proportions of the thick and thin parts. The solidified work is unique.

A terracotta copy is a work produced from clay pushed or poured into a mould. Such sculptures are cheaper and are less detailed than the preceding ones. Thanks to the legislator, who is surely not a sculptor, since 1968 the tax concept of originality was also extended the technical and modeling originality of terracotta sculptures. It offered the status of original works to moulded terracotta works, up to the limit of 8 copies. This imbroglio has opened the way to numerous abuses.

From a stylistic point of view, the work is original where it contains the characteristic stamp of an artist, which renders it unique in the eyes of a connoisseur. Prior to 1968, the original copy of a sculpture in bronze or any other material was not limited in time or by the number of copies.

Notes

1. Fleeing the wrath of Juno, Leto traverses Lycia with her twins, Diana and Apollo, children of Zeus. Under a hot sun, thirsty, she wanted to drink water from a marshland. Farmers who were gathering bulrushes and algae stopped her by swearing at her and stamping their feet to render the water murky. Spitefully, faced with the imploring mother, they brought up soft mud by jumping around in the water. The goddess’s anger made her forget her thirst and she implored Zeus, raising her arms to the skies: “let us live forever in your pond!”. Her wish was granted by the master of the universe: they were changed into frogs and newts. (Ovid, The Metamorphosed, VI, 361-385.)

2. Article 71-3 of Appendix III to the (French) General Tax Code: “Original works of art are considered to be (…) productions in any statue, sculptural or assembling art material, where such productions and assembled works are produced entirely by the artist; casts of sculptures limited to eight copies and supervised by the artist or his successors”.

3. Decree 81-255 of 3 March 1981, Art. 9: “Any facsimile, mould, copy or other reproduction of an original work of art within the meaning of Art. 71 of Appendix III of the General Tax Code that is produced after the date of entry into force of this Decree must bear, in a visible and indelible manner, the mark ‘Reproduction’.”

4. “Mr Lavédrine reminds the Ministry of the Budget that (…) artistic works are kept by the artist himself or his successors, that they cannot be traded and can be kept by the artist (or his heirs) only for his personal collections or work (…)”. OJNA, 8 Dec. 1978/Lavédrine, 10 May 1978, no. 1097.

5. Cf. Wooden sculptures by Gilles Perrault, ed. H. Vial, Dourdan.

6. An undercut shape cannot be removed from a mould without being broken and remains inside a rigid plaster mould. This same shape can be removed only if the person creating the mould makes at least two pieces in the undercut when creating the plaster moulds.