Expert modern and contemporary art reports often confront not only contrary opinions from heirs and rights-holders but sometimes even the artists themselves when they are mistaken in their authentication of works presented to them. This article provides a non-exhaustive summary of such difficulties and possible solutions.

La Revue Experts No. 60 – 09/2003 © Revue Experts

For the neophyte, this dripping appears to be that of the American precursor of the genre, Jackson Pollock, who died in 1956.

Unfortunately for the owners of this recently discovered abstract work, its author is considered to be merely a European follower of the American artist who created this form of painting by projection in 1947. The value of the work is therefore affected as, if experts had attributed the painting to J. Pollock, it would have found a buyer at €6 million but, being the work of J. Brown, it will not exceed €10,000.

1. In the artist’s lifetime

Numerous art lovers, misled as to the authenticity of modern works of art, become interested in contemporary art. They sometimes buy works directly from the artist, persuaded that they will not longer be taken advantage of.

The work of a contemporary artist evolves on a daily basis. A collector can, if he wants, follow such progression and even become involved in it. The purchasing of a unique work directly from the artist or a gallery owner either during or just after completion of the work constitutes the best guarantee of authenticity.

The work thus holds a historical dimension to which he contributed and perhaps even influenced. That dimension is not fixed; it increases if the work is the subject of news reports and exhibitions, ultimately becoming part of the legendary status of the artist.

A personalized dedication both increases the historical attractiveness and definitively determines the uniqueness and authenticity of the work. To use a well-known expression used by gallery owners and borrowed from the diamond industry, it becomes ‘blanc-bleu’, here meaning that it is of irreproachable authenticity.

The purchase of a work created several decades ago can, on the other hand, raise problems; the artist no longer recognizes his own work either because he has forgotten or because he considers the work no longer worthy of bearing his name.

Several well-known cases of artists with an abundant production, such as Picasso, have made the news, but they remain extremely rare and do not have any repercussions on the art market.

The same does not always apply to elderly artists who are the prey of swindlers: the new spouse, a family in need, a profiteering friend, devoted personnel…

The classic modus operandi consists of fraudulent conversion. The person who has the confidence of the artist presents him with a fake, claiming that he ‘forgot’ to sign the work, or imitates his signature and has him draw up a certificate of authenticity.

The Parisian, bronze from overmoulding, signed P. Gauguin, circa 1990.

Fake painting signed ‘Sisley’.

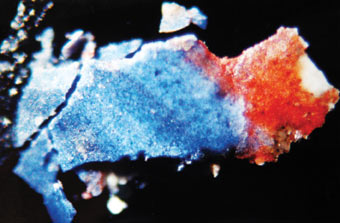

Examination under ultraviolet rays of the fake Sisley, the dark violet areas indicate where the painting has been the subject of a recent restoration

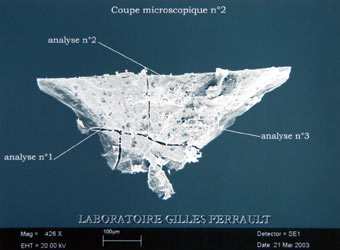

Microscopic cross-section of a fake Raoul Dufy painting.

Scanning electronic microscope photograph of pigment sample from a painting by Chirico. The textures analysed by EDS probe are identified by the arrows.

Microscopic cross-section of a sample from a fake Picasso.

In his supportive work on Fernand Legros, a well-known counterfeiter operating between 1960 and 1975, Alain Peyrefitte relates that Legros produced works comprised of parts copied from various authentic works that were so well copied in both form and style that various artists acknowledged them as being their previous work…

That era has passed, as nowadays artists do not exist without a ‘coach’, whether gallery owner, expert, art critic or historian, who photograph, note, analyse and categorize everything. Rigorously produced, such inventories result in catalogues raisonnés that raise the works to sacrosanct status, reducing those not figuring in them to nothing.

The 21st century is that of globalization, communication and documentation. Contemporary artists have understood this and favour the use of computers to distribute their message and perpetuate their works. For expert reports on the work of a living artist, therefore, his opinion should be obtained and his archives consulted. Either the disputed work is found or it is unknown.

2. From the living person to the widow and rights-holders

After the death of the artist, the author’s rights pass to his direct heirs, unless he has nominated an art or legal professional in his will. The heir receives income from the work for a period of seventy years under the rights to reproduce and present, a percentage from auction sales, etc.

Even the image of the artist himself can produce revenue, such as those of Picasso, Van Gogh and other famous names.

Another non-negligible source of income for the family of the deceased consists of producing expert certificates. On average, €450 to €1,500 needs to be spent, depending on the artist, for a certificate from a rights-holder who merely refers to his archives.

If the work is not in the archives, a true obstacle course awaits, the journey for which can last many years.

Before commencing, it should be understood why the work is not listed in the family archives. Was it a work produced by the artist in his studio without the knowledge of his family or friends? Was it stolen, forgotten or is it simply a fake?

Two Titans, fake bronzes in moulded resin after Vase of the Titans by Rodin but signed by his employer at the time: Carrier-Belleuse.

In numerous cases, works offered to mistresses are not listed because the heirs prefer to amputate the work from the deceased rather than acknowledge and pardon his misbehaviour.

It is often necessary to wait until the death of the spouse before recommencing the process of authenticating the work on offer. Where the financial stakes are very high, however, such disputes end up in court with the appointment of one or more experts. When confronting rights-holders, generalist experts must accumulate historical, stylistic, technical and scientific proof to support their opinion.

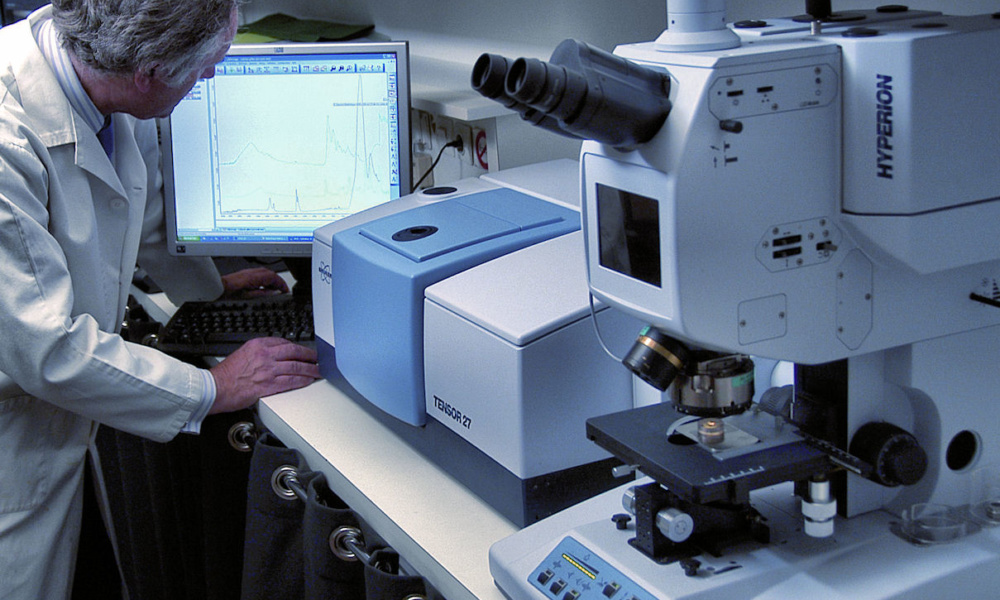

If the painting is a fake that was produced during the lifetime of the artist by another artist who copies the same gestures on his canvas, the same processes for creation and the same pigments, the task will be very difficult for the court-appointed expert. The cost of his task will reflect this, as he must rely on one or more forms of proof by using all current scientific means at his disposal: reflectography under ultraviolet or infrared rays, radiography, analysis of components by x-ray fluorescence, etc.

Radiography using x-rays clearly shows the non-visible preparation used for a painting on canvas or wood. Until the 1980s, counterfeiters did not think to copy the outlines of the first brush strokes of the painting that later become masked by the visible layer.

Idem for the lack of brush stroke vigour that is characteristic of counterfeiters and that can be seen using radiography. Such examinations are only usefully, however, when compared with examinations carried out on authentic works under the same conditions.

If his conclusion is that the work is clearly the work of the artist in question and he provides irrefutable proof, the heirs to this parallel aspect of the artist’s life may be successful in court but not necessarily in the catalogue raisonné held by the rights-holders and the expert on the artist.

3. Second generation heirs

Nobility, substantial fortunes, well-known artists, their family and entourage inculcate their descendants with the importance of inheriting. The child is cradled in family legends: Norman or crusader ancestors for some, the names of personalities in politics or finance for others. In the artist’s family, the works of the grandfather that are hung on the walls remind the family of the importance of inheriting. All those dreams of a glorious past, constantly recounted, create solid roots. What, then, is more natural than for a descendant to revive his ancestors and base his reputation on this bloodline gift?

Eve on a rock, after Auguste Rodin, bronze from overmoulding produced in 1989

Loie Füller, after Raoul Larché. Gilded bronze from overmoulding produced in large quantities between 1985 and 1991.

Woman, after Diego Giacometti, extract from The Couple, bronze from an overmould produced in 1989 after the death of the artist in 1985.

The grandchildren, great-nephews and cousins often never knew the famous artist but the link incites publication of a catalogue raisonné and management of his work: films, exhibitions, catalogues, derivative products and expert certificates. Which means, if successful, wealth, glory and honours. While the heirs of Picasso have been able to share the task, honours and fruits, certificates are issued only after consultation of archives by a committee.

While the testamentary rights-holder of Maillol, Dina Vierny, skillfully and faithfully manages the work of the master artist, some artists, such as Camille Claudel, who do not have direct descendants, do not have such luck. Some of her great-nephews produce bronzes via unscrupulous intermediaries well known to the fraud office, certify works and, in particular, accredit their production without consultation with the other heirs. It is easy to understand that such people have an interest in appearing in the lists of art experts in order to better control their post-mortem production and avoid the truth coming to light.

The ensuring rivalries benefit neither the work nor art lovers, who are no longer sure of which expert is a true authority. Due to the extent of the self-interested battles in such specific cases, significant care should be taken.

What, for example, should be made of the solid gold Waltz sculptures, a dozen reduced-size models having been produced by the Monnaie de Paris in 1990 for the benefit of the sole heir of Camille Claudel, and the workmanship in which is so clumsy it betrays the memory of the artist?

Such atypical miniatures, which the artist would not have tolerated, are considered to be authentic casts by the person who placed the order but illicit by the remaining heirs. They owe their existence only to the fact that Prince Charles bought one of the models and offered it to a friend bearing the same first name as the original artist. For reasons of State, no proceedings were ever brought in court. So what will happen when the owners of the other examples decided to auction the model that they bought in 1992 for 1,200,000 francs, ie, approximately €183,000?

And the paintings signed C. Claudel, one of which was even sold by the nephew of the artist as having been painted by his aunt when in fact the paintings are by an unknown artist, Charles Claudel?

If such cases emerge in court, we can but hope that the court-appointed expert, independent of personal and family interests, will be able to provide impartial advice that will have authority throughout the art world.

Another example of expert certificates produced by rights-holders concerns the work of Baldaccini César, who died in 1998. Already, more than thirty-five French and European galleries have sold fakes produced by two counterfeiters who ‘guarantee’ their work through the production of certificates of authenticity drawn up by certain heirs.

And, lastly, an example of an expert licensed through a family association, that of Mr X, lover of the sister of an artist who died in the 1970s. Access to the family archives has enabled him to produce a catalogue raisonné. Any work not contained in it is rejected. The brave man, who does not have a background in the field but had the patience, together with the artist’s sister, to classify the family documentation and place a caption under each photograph, claims to be an expert in the work of his ‘brother-in-law’ and is held out to be an authority even though he is incapable of distinguishing an acrylic from an oil painting.

Producing an expert report on works of art requires a lifetime of research into history, styles and techniques. The high-society expert reports of the 20th century no longer exist. The authority of the inheritance cedes when faced with proof. Sentiments and attractively worded phrases are confronted by scientific reality. The rigour of research work ultimately takes precedence over appearances.

The certificates issued by heirs of modern and contemporary artists still often remain an obligatory passage but are also the most controversial.

Those that are drawn up by experts who are specialists in the work of the artist in question are less controversial. But, as so accurately stated by F. Duret Robert in his book Marchands d’art et faiseurs d’or: “the only good scholar is a living scholar” because, as soon as he rests in peace, his successor, in order to confirm his reputation, constantly and directly questions certain attributions of works and publishes a new catalogue raisonné.

Ostrich, after the work of Diego Giacometti, gilded bronze from an overmould produced in 1991.

Posthumous miniature of The Waltz by Camille Claudel in solid gold.

4. Falses prices, from lawful methods to abuses

How can the popularity of a contemporary artist be false? All it takes is for a work of the artist to be put up for public auction in order to his financial value to be confirmed, or so thinks the honest man. The professional will smile. The seasoned art lover will reply that all that is needed is consultation of the directories of prices of all works of artists sold at public auction worldwide in order to know the precise value of a drawing by E. Degas or a painting by Combas.

His reasoning is correct in relation to the work by Degas, who died in 1917, whose reputation extends worldwide and who, especially, benefits from the current popularity of works from the end of the 19th century and impressionists.

For an artist like Robert Combas, who was born in 1957, his style shows a lack of experience. The works of Combas reached €100,000 between 1985 and 1990 but currently sell for ten times less that price. The overpricing came from being popular at the time, encouraged by friendly protection from the Minister for Culture: a lawful method so long as it does not become excessive favouritism.

A buyer who follows the progression of an artist’s popularity can be fooled by false prices artificially maintained by the gallery owner that manages the artist’s work. The usual process is to affix high prices in the gallery and to have works by the artist, as provided by the gallery owner or art lovers, purchased at such amount, as a minimum, in auction houses. In order to do this, the gallery owner must have certain amount of stock as, after several years, he risks being exceeded by his customers who, counting on making a profit, present their paintings for auction.

So what stance should the court-appointed expert adopt when he is instructed to estimate the value of such works? Should he bravely inform the court of the artificially raised prices the fragility of which is inversely proportionate to their ascension? Clearly yes, but with a considerable amount of discernment and proof so that he does not suffer any low blows from the disadvantaged party.

The artificial prices maintained by the gallery owner continue when the artist acquires an international reputation, takes part in important expositions and is exhibited during his lifetime in prestigious American and European museums of modern art.

With his reputation ensured, the prices for his work will be easily maintained. Such is the case with the works of J. Miro, G. Braque, A. Giacometti, F. Léger and other artists whose works are perfectly managed by the Maeght Gallery. The creation in 1964 of the Marguerite and Aimé Maeght Foundation by André Malraux in Saint-Paul-de-Vence rewards gallery owners and artists and contributes to the glamour of French artists. The works of artists that they have supported has led to an increase in prices that has never faltered.

5. Settlements and court claims

Disputes over the authenticity of the work of a contemporary artist relate to counterfeiting and the offence of making illegal copies.

Where the owner of a fake or supposed fake becomes aware of his disappointment, he will request that his vendor cancel the sale and return his payment, sometimes with interest paid. Who is then surprised to find that, in 95% of cases, the amiable vendor, a clearly well-established professional with a reputation for being courteous and honest, treats his request with derision and strongly criticizes the qualities of the expert who dared claim that the work is a fake!

Trojan horse, after S. Dali, posthumous bronze produced in 1990, fake from an overmould.

The vendor is sure of the origin of the work and the expert certificate that accompanies it and if the unfortunately buyer still has any doubts and is willing to bring court proceedings, they will cost him dearly. Because not only will he lose but he will be covered in ridicule and will most certainly be ordered to pay damages, interest and proceedings costs under Art. 700…

It is, therefore, very rare that a trader or auctioneer immediately cancels a sale on the basis of such proof. This is a persistent utopia, well maintained by the interested parties.

The unhappy and rejected buyer, vexed by such turn of events, files his proceedings in court and applies for the appointment of an expert.

Such claims must be sent either to the public prosecutor where the offence took place or filed directly with the national gendarmerie or criminal police force the head office of which is in Nanterre*. That service has national jurisdiction, which has led to an increased effectiveness in dismantling counterfeiting networks.

The claims are taken into account by the public prosecutor only if there is a significant probability of the existence of counterfeiting and/or fraud.

The error in the substantive qualities of the item falls within the civil jurisdiction only, but the two proceedings can be heard simultaneously.

A claim on the basis of fraud will be upheld if the plaintiff (the buyer who was misled) can argue that the vendor was acting in bad faith and with complicity in the acts that defrauded the rights-holder. He can also extend the same proceedings by bring a charge against X, proving, prior to filing his claim, that the owner is but a link in a chain of participating parties.

Pastiche by V. Kandinsky, painted circa 1950.

NOTE

- Criminal Police Head Office (D.C.P.J.), 101 Rue des Trois Fontanot.